This is the thirty-fifth in a series of posts that report by Dr Robert Ford, Dr Will Jennings and Dr Mark Pickup on the state of the parties as measured by opinion polls. By pooling together all the available polling evidence the impact of the random variation each individual survey inevitably produces can be reduced.

Most of the short term advances and setbacks in party polling fortunes are nothing more than random noise; the underlying trends – in which the authors are interested and which best assess the parties’ standings – are relatively stable and little influenced by day-to-day events. If there can ever be a definitive assessment of the parties’ standings, this is it. Further details of the method used to build these estimates of public opinion can be found here.

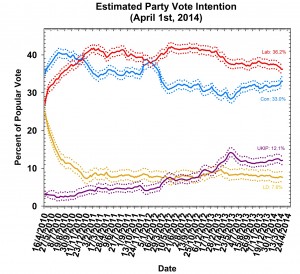

This month’s Polling Observatory is the first since the March budget, widely reported to have driven a bounce in support for the Conservatives. There is certainly evidence of a narrowing in the gap between the top two parties: our estimate puts Labour on 36.2%, down 0.8 percentage points on last month, and their lowest share since the end of 2010.

The Conservatives are up on 33.0%, up 0.9 points on last month and their highest share since early 2012. This leaves the gap between the parties at 3.2%, the lowest we have recorded since the parties briefly drew level in the aftermath of David Cameron’s European treaty veto in late 2011. It seems our speculation about a possible “voteless recovery” last month may have been premature. Meanwhile, in the undercard fight, UKIP come in at 12.1% this month, down 0.6% on last month, while the Liberal Democrats post a figure of 7.6%, up 0.4% on last month’s score.

The Conservatives’ renewed strength in the polls may owe something to a well-received budget from George Osborne, but when we take a longer view it becomes apparent that this latest narrowing is in fact the a continuation of a very gradual trend that has been proceeding, in stop-start fashion, for more than a year – as our excellent colleague Anthony Wells noted in his year-end review.

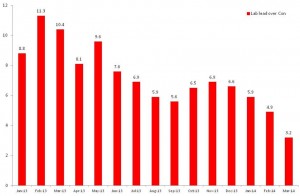

In the early months of last year, Labour leads over the Conservatives were in double digits. This fell to under six points in the summer, before rebounding slightly in the autumn. Since November 2013, though, the narrowing has continued, and the lead has fallen from just under seven points to just over three.

Regular readers of this blog will know that we are cautious about identifying trends in what is often stable opinion, and also wary of using figures on polling leads, which are subject to more volatility and random variation. The underlying pattern here is however clear – the gap between the top two parties is steadily narrowing.

Our main chart suggests this is the product both of rising Conservative support and falling Labour support, and also suggests that this is happening despite no decline in support for UKIP, who many argue are the main cause of recent Conservative weakness

Labour leads over the Conservatives since January 2013

This slow but steady change in public opinion is not, however, the product of short term shifts in the political weather – the gentle ebbs and flows in public opinion over the Parliament do not have much relationship to the torrent of scandals, gaffes, policy announcements and message battles which constitutes the day to day world of politics for those in the media.

This disconnect between the narratives about political events that are popularised by politicians and the media, and the slowly shifting tides of public opinion highlights the two-speed nature of politics. In Westminster, politics is a frantic day-to-day activity, conducted in the merciless glare of a 24 hour news cycle. Out in the country, politics is a marginal interest, on the fringes of attention, and opinions change slowly.

Those who make a habit of following political stories on newspaper front pages – or via highly charged political Twitter feeds easily forget that most voters are paying little to no attention to the events which are filling their days. Even major political set-pieces like the budget, Prime Minister’s Questions, or the Clegg-Farage debates barely register with many voters. Indeed, most of the population are at work during PMQs, unable to tune in to a television or a politics live blog, while the vast majority had much more interest in the latest goings on in Albert Square or Coronation Street than the duelling rhetoric of Nigel and Nick.

Even economic news, which is of more immediate interest to many voters, tends to trickle down as a gradual process of diffusion, either in a general sense among the public that things are getting better or worse for the country or more directly as people feel better about the pounds in their pocket, and more eager to spend them. In practice, the fallout from political events is usually slow and sluggish, as it takes a long time for voters to notice and respond to things which are a long way from their everyday concerns.

Shifts in public opinion therefore tend to take place slowly, over long periods of time (with rare, but important, exceptions such as the Cameron veto and the “omnishambles” budget). Political commentators, however, exist entirely in the “high frequency politics” world, and interpret every day’s and week’s events in terms set by this world, projecting them onto the wider public, whose indifference is so far from their own everyday experience that it is hard for them to keep it in mind. Every minor event is expected to produce a sharp public reaction and every momentary twitch in the pulse of public opinion is attributed to the stories attracting Westminster buzz.

As we write, much ink is being spilled over the public opinion implications of Maria Miller’s expenses, yet there is no sign that this is having any impact on the polls, nor should we expect it to when most voters have only a sketchy understanding of who Ms Miller is or what she is supposed to have done. This may change as the story gradually diffuses through the electorate, or if it takes a new turn. More likely, however, is that it will simply come and go, like many earlier stories before it, without leaving any lasting mark, aside perhaps from intensifying a little the “pox on all your houses” sentiment which has helped to fuel the rise in UKIP support.

It is important to bear in mind that the important, and lasting, changes in public opinion take place gradually, often too slowly to perceive without the benefit of months of data, because as election fever takes hold in the Westminster village, the focus on “fast politics” will become ever more intense.

There will be many moments and many stories that are presented to us as ‘game-changers’ or turning points. In most cases they will be nothing of the sort, while the real action takes place away from the noisy slapstick comedy playing out on the news channels. Millions of voters will begin settling on their choices, nudged this way and that by forces which are, to some extent, predictable.

The regularity of the tidal forces which move the “slow politics” of voters’ shifting opinions allow us to make modestly informed forecasts about the direction public opinion will take next, based on the lessons of history. Such forecasts are inevitably limited, particularly this far out – every election is in some respects unique, and we only have polling data for about 15 previous election cycles.

Nonetheless, they tell us something useful about the likely direction of public opinion, and do better than guessing the outcome based on where opinion is now. Next month, with exactly a year to go until the general election, we will unveil our first forecast of the most likely state of public opinion on polling day next year, and how this will translate into seats in the House of Commons.

There is still a long way to go, but our initial analysis suggests that the narrowing over the past year is in accordance with past trends. Tune in next month to find out if we expect it to continue.