As the UK embarks on rolling out new digital and mobile capacities in the fight against COVID-19, other countries may serve as bellwethers for potential issues. In this blog, Dr Michael Prentice, Research Fellow in Digital Trust and Security, discusses privacy issues that arose in South Korea’s technology-driven response to the COVID-19 outbreak and how this could inform the UK Government’s response.

- South Korea is generally held up as an example of a strong technology-driven, data-transparent response to stemming the COVID-19 outbreak.

- This highly transparent response also raised concerns around data leaks, social paranoia, and stigmatisation.

- As a result, South Korea is now moving away from its early emphasis on high-information contact tracing.

- UK policymakers should be aware of the potential pitfalls from South Korea and strike a balance between what is necessary for public health and what information is not just personally identifiable, but socially identifiable.

South Korea is generally held up as an example of a strong technology-driven response to stemming the COVID-19 outbreak. The country’s efforts at tracking the spread of the coronavirus through contact tracing were praised. Beginning at the peak of the outbreak in February, South Korean citizens received hour-by-hour detailed information on when and where potential infected persons were located via text messages, Facebook, domestic blogs, and Twitter. Citizen-based participatory efforts at visualizing the spread of movement via maps and apps allowed citizens to check whether they had crossed paths of suspected infected patients. This capacity has relied on a strong infrastructure for IT and surveillance and social acceptance for public monitoring.

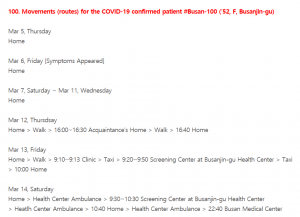

Figure 1. Example of detailed ‘contact tracing’ released in English by the city of Busan

Source: Busan English Broadcasting

Invasions of privacy?

However, as reported by the BBC and The Guardian, this information-robust response has spurred concerns about privacy risks. South Korean media (in Korean) have been rife with concerns that for many, the potential invasions of privacy are more “terrifying” than contracting the disease itself. A district office in Seoul had to issue a public apology for leaking personal information of a potential patient, and a health centre in the city of Pohang is under investigation for releasing a patient’s name and address. These offices are likely to face fines for mishandling private health data.

Like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) instituted in 2018, South Korea’s Personal Information Privacy Act (PIPA), instituted in 2011, strictly protects ‘personally identifying information’ (PII) as key points of protection for organisations that collect or handle individual data. Individual leaks of identifying information, such as name, address, workplace and religion, pose risks to individuals, especially those in bio-vulnerable circumstances.

Judgements on (in)appropriate behaviour

One of the lessons the South Korean case raises is the broader circulation and utility of non-personally identifying information, such as ‘movement’ or ‘contact tracing’ data. That kind of data does not reveal specific PII, but even anonymised, de-identified information from highly transparent sources can pose social risks.

One risk is the revelation of what we might think of as socially identifying information, such as recognisable social types, places, or actions. As the Chosun newspaper in Korea reported, a person who was reported to have visited a hotel and a plastic surgeon’s office was ridiculed online for inappropriate behaviour. And as the Washington Post noted, one million citizens in the city of Daejeon received text messages about a visit by an infected person to a karaoke bar at midnight, which led many to assume the person was having an affair.

Another evident risk is being dubbed “secondary damage” from revelations of overly descriptive geographic patterns. Yonhap news reported that an apartment building in the city of Incheon had an outbreak owing to a small cluster of members of the Shincheonji church (the group through which the largest outbreak in Korea occurred) who resided there. The apartment building was labelled “Shincheonji apartment” online, stigmatising those who lived there but who were not church members. Apartment names, small neighbourhoods, and franchise businesses can face this kind of secondary or associational damage.

Reducing secretism

The emphasis on rapid, widespread, and accessible data on movement of patients from the South Korean government is not a cultural disposition; rather it comes from the response to the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2015. At the time, the government was criticised for not publicising hospitals where patients were being treated. A 2016 White Paper (in Korean) from the Ministry of Health and Welfare advocated for the swift release of movement information to combat accusations of bureaucratic secretism.

However, the actual level of technological coordination involved in tracking COVID-19 – said to involve credit cards, mobile GPS, transportation cards, and CCTV – has been overstated. Coordination was actually hampered by privacy regulations and inter-organisational logistical issues. Many of the actual ‘movement reports’ were assembled from oral reports, not big tech; they also included intimate details that are not personally identifiable, but not necessary to report either. Such reports may make the government accountable to the public, but they may not be the most useful for sharing information in widespread crises.

The National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) has recently issued a warning about the excessive nature of information about private lives being released, leading to harms such as criticism, mockery, and revulsion. This may increase feelings of paranoia as the stigma associated with the virus may linger longer on places and people than the virus itself. South Korea has issued new guidelines as a result.

What UK policymakers should be aware of

The South Korean case indicates that the public can become over-interested in even anonymous information. This can lead to increased paranoia, stigma by association, or panic around certain social groups, and alert fatigue. While the UK and other countries may attempt to model the success of public health strategies used by South Korea, Singapore, or Israel, those countries’ policies are also shifting as the pandemic has evolved. Korea, for instance, is moving away from contact tracing, to more generalised quarantine guidelines for the public. A new announcement to coordinate better amongst 27 public and private organisations to deliver rapid contact tracing information will be used primarily for health authorities’ analysis and response, not for public information.

NHSX is currently assessing a new contact tracing app. UK policymakers should be aware of the potential pitfalls and over-promises from South Korea and strike a balance between what is necessary for public health and what information is not just personally identifiable, but socially identifiable. The UK already has experienced instances of anti-Asian sentiment in the early stages of reporting, and social fears or geographic stigmatisation could be confirmed or exacerbated through the specificities of information design. Even well-designed apps can provide a false sense of safety if only a limited segment of the population downloads it. (Korea for instance has only had a 35% success rate in having overseas travellers download a self-isolation monitoring application.)

South Korea’s privacy regulations include a special article that waives certain penalties and restrictions on the temporary handling of private data during a public health crisis. Yet they have not breached other privacy norms, such as making quarantine/tracing applications mandatory. They have even promised to delete any collected information after it is not needed. Therefore, while UK organisations should follow existing GDPR requirements as well as updates from the European Data Protection Board and the ICO, they should exercise caution in broaching privacy norms and expectations, even in a time of crisis.

Take a look at our other blogs exploring issues relating to the coronavirus outbreak.

Policy@Manchester aims to impact lives globally, nationally and locally through influencing and challenging policymakers with robust research-informed evidence and ideas. Visit our website to find out more, and sign up to our newsletter to keep up to date with our latest news.