The post-Christmas lull is deemed to be a particularly lonely time for many individuals. As ‘Blue Monday’ fast approaches, Natalie Cotterell, PhD student in Social Statistics, discusses the challenges to successfully tackling loneliness.

- Approximately 14% of the UK population has reported that they often feel lonely, and this number has been found to rise to up to 73% when considering those aged 50 and over.

- The majority of interventions place all of the responsibility on the individual without taking into account the wider environment.

- A holistic approach is necessary if we are to succeed in preventing loneliness in older age.

‘Blue Monday’ is the third Monday in January and has been labelled the most depressing day of the year, according to mainstream media. It is calculated using several factors including: bad weather, high debt levels, the amount of time since Christmas, time since failing New Year’s resolutions, low motivational levels, and the feeling of a need to take charge of the situation. However, critics argue that feeling depressed or lonely are not dictated by a date but are prevalent across the population all year round. Recent research supports this, with 14% of the UK population reporting that they often feel lonely. This has been found to rise to up to 73% when considering those aged 50 and over. This suggests that certain groups are more at risk of loneliness.

It is important to tackle loneliness as it can have detrimental health effects that become more pronounced in older age. Those who are lonely are at an increased risk of a number of life-threatening conditions, including cardiovascular disease, depression, and dementia. Furthermore, health issues arising from loneliness have been found to lead to an increased use of health and social services, including a higher number of GP consultations, highlighting the economic cost of loneliness. This further emphasises the importance of maintaining social connections throughout the life-course.

In order to successfully tackle loneliness, there are three main challenges to overcome: identifying those at risk; assessing loneliness; and developing effective interventions to prevent loneliness in later life.

Challenge #1 – Identifying individuals at risk of loneliness

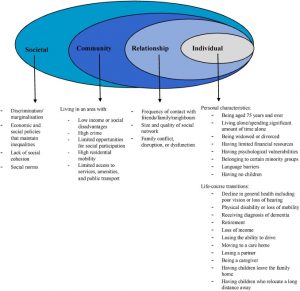

Loneliness often remains undetected as it is not routinely assessed in settings that are well-placed to identify individuals who are at risk. Frontline professionals working in primary care could play an important role in preventing loneliness as they regularly interact with individuals who are at risk. The UK Government have recognised this in the loneliness strategy it launched in October 2018, stating that all GPs in England will be able to refer individuals experiencing loneliness to community activities by 2023. First, however, frontline professionals such as GPs must be able to identify loneliness and its risk factors. The image below enables us to view loneliness as the outcome of interaction among multiple risk factors at four levels: individual, relationship, community, and societal.

Fig. 1. The ecological framework: examples of risk factors for social isolation at each level

Challenge #2 – Assessing individuals at risk of loneliness

The ‘Making Every Contact Count (MECC)’ approach encourages frontline workers to have brief conversations with individuals about how they can make positive improvements to their wellbeing. The MECC approach could act as an initial assessment of an individual’s risk of isolation, helping professionals to decide whether onward referral is appropriate.

If an individual is considered to be at high risk, further information may be collected using validated assessment tools such as the Lubben Social Network Scale. Such scales assess the quality and quantity of an individual’s social connections. However, these tools were designed for use in research and may not be practical in high-pressure environments such as healthcare settings. This highlights the need to develop accessible methods for assessing those at risk of loneliness.

Challenge #3 – Designing effective interventions

Six types of interventions have attempted to tackle loneliness in later life, all of which have had limited success. These include working with: individuals, groups, services, technology, neighbourhoods, and social structures. Group interventions are the most commonly used, yet there is little evidence of their effectiveness in reducing loneliness in older adults. It is clear that quality remains an issue when designing and delivering interventions. Most interventions lack robust evaluation; few interventions assess an individual’s level of loneliness pre- and post-intervention. This makes it difficult to draw conclusions about their effectiveness.

Furthermore, most interventions place all of the responsibility on the individual without taking into account the wider environment. For example, interventions working with social structures are the least commonly used; yet they arguably have the greatest potential to have wide-reaching effects at the population level. Such interventions include promoting positive ageing through policy and attitudinal change. This suggests that we need an increased awareness of the importance of the wider environment in preventing loneliness.

Policy recommendations

The loneliness strategy proposed by the UK Government has promised to lay the foundations for change in tackling loneliness. This is a reassuring first step towards building a more connected society. It is recommended that the strategy and future policies prioritise the following:

- A cultural change from cure to prevention of loneliness. This is required to improve the effectiveness of interventions. There should be a focus on designing interventions targeting key transition points throughout the life-course, aiming to build resilience for managing major changes associated with retirement, bereavement, and chronic ill-health.

- Recognition of the heterogeneity within the population. Existing interventions and policies largely ignore diversity with only a limited number targeting the specific forms of isolation experienced by minority groups. Given the increasing diversity and ageing population, there is an urgent need to design more targeted programmes.

- More robust evaluation of interventions. This will improve the quality of future interventions, helping to draw firmer conclusions regarding their effectiveness for preventing loneliness.

There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to preventing loneliness. A holistic approach should be adopted when designing and commissioning services, encouraging national, regional, and local authorities to work together with communities to understand the context of loneliness. So, why wait until ‘Blue Monday’ to connect with someone? We can all help to prevent loneliness by leading more connected lives.