Dr Ingrid Storm argues that economic concerns about immigration are related to financial insecurity.

In the wake of the Syrian refugee crisis immigration is high on the political agenda throughout Europe, sharply dividing public opinion. Anti-immigration rhetoric often paints a picture of immigrants as “stealing jobs” or “scrounging” on the welfare system, arguments that can be damaging not only for the sobriety of the political debate but also for the picture they paint of immigrants and ethnic minorities in general.

To understand why such economic concerns gain currency it is important to ask whether they arise from genuine economic worries, or whether they are simply a means of expressing racial prejudice. The recent financial crisis offers a unique opportunity to examine this question. If increased economic hardship leads to anti-immigration attitudes we should be able to see it in the period since 2008 when economic growth has stagnated and unemployment has grown dramatically in many European countries.

To examine this hypothesis I have been looking at the European Social Survey (ESS) which recorded the immigration attitudes of more than 250,000 people between 2002 and 2012 across 31 countries. Respondents were asked whether they thought immigration was good or bad for their country’s economy, and whether they thought immigration enriched or undermined cultural life in their country.

Economic concerns may be motivated by insecurity about how labour market competition, salary levels and welfare distribution are affected by population change. Whether or not these are valid arguments against immigration, they can be seen as a rational cost-benefit calculation based on economic self-interest.

Cultural concerns, on the other hand, can be motivated by changes in national identity or local communities, and include worries about differences in language, religion, and cultural habits, as well as ethnicity and race.

The study found that these views were closely related. Agreeing with one argument makes you much more likely to agree with the other. Many studies have shown that perceived threats to economic resources may lead to stronger identification with one’s own ethnic and national group. Conversely, people may justify their racial bias with economic arguments. An analysis of the data shows that people who are employed, satisfied with their household income, and satisfied with the wider national economy, are more likely to have positive attitudes to immigration. Both personal economic circumstances and the national economy make more difference to economic than to cultural concerns about immigration.

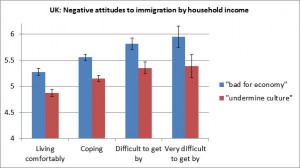

The relationship for Europe in general can also be found to hold within most individual countries. Immigration attitudes are significantly more negative among people who find it difficult to get by on their income, and this is when we hold constant many other factors that could influence the results such as level of education, employment, gender and age.

Figure 1

ESS UK 2002-2012, N= 12359. Predicted probabilities after controlling for survey year, age, gender, family immigration history, education, employment, household composition etc. in OLS regression model. The error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Both questions had answers on a scale from 0-10 where higher values are more negative.

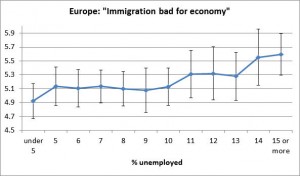

It is not only individual economic satisfaction which predicts immigration attitudes. We also see similar relationships at the country level. Across Europe, countries with lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and higher unemployment rates have more negative attitudes to immigration on average, particularly with reference to economic concerns about immigration.

Figure 2

ESS 2002-2012, N= 148671 Predicted probabilities after controlling for survey year, age, gender, family immigration history, education, employment, household income etc. in a multilevel regression model. The error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

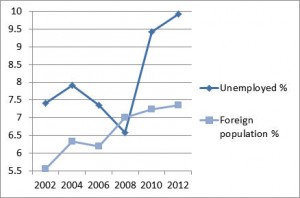

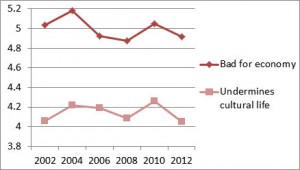

Over time, we also find that changes in GDP and unemployment predict changes in attitudes in Europe. Opposition to immigration grew during the financial crisis, as many European countries went into recession and unemployment levels increased, but this has since stabilised.

Overall anti-immigration attitudes decline during periods of economic growth, while increases in unemployment are associated with growing concerns about immigration. Unemployment increased most dramatically in the recession from 2008 to 2010, while there was a smaller rise between 2002 and 2004. But in both these periods, attitudes to the economic effects of immigration became more negative. In contrast, immigration (measured as changes in the proportion of foreign citizens in the population) had no significant relationship with the attitudes. Opposition to immigration declined from 2004 to 2006 when immigration levels were growing the most, and unemployment was decreasing.

Figure 3

ESS 2002-2012 (Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, Great Britain, Hungary, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Sweden, Slovenia)

In general then, financial hardship and the risk of unemployment is associated with lower support for immigration in Europe both within and between countries and over time.

The results indicate that economic concerns are a genuine reason for many who oppose immigration, but also that they are closely associated with more negative attitudes to the cultural impact of immigration. The relationship between economic insecurity and economic concerns about immigration suggests that anti-immigration arguments could win support in part by acknowledging economic hardship as a problem.

The counter-argument that immigration leads to economic growth in general, can be hard to swallow for those who experience genuine lack of resources, and those who wish to influence public opinion should take this into account. Allowing insecurity to inspire and legitimate prejudice could affect not only political decisions about immigration, but also lead to more general bias and discrimination against ethnic minorities.

- The views expressed in this article are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).