Why do Conservatives try so hard to increase their ethnic diversity while Labour takes minorities for granted? It all depends on who their target voter is. Labour’s target voters thought less of the party when they knew about its ethnic diversity, Conservative’s target voters were the opposite, explains Maria Sobolewska.

For political parties the question of ethnic diversity is predominantly a strategic one. A party’s ethnic diversity could help it win votes, but it could also lose it votes. For decades, constituency-level data seemed to show that ethnic minority candidates did worse than white candidates of the same party (for a recent summary see here) and individual-level data largely confirms this is especially the case for Muslim candidates.

Increasing a party’s diversity, in the face of the ethnic minority candidates seemingly losing votes, has therefore become a conundrum. Why do the parties do it, and why do some of them do it more than others? The obvious answer has been usually the need for the party to win the ethnic minority vote. But, while there are 74 constituencies where ethnic minorities form more than 20% of the electorate and thus in which they could be the pivotal voters, attracting the white majority of voters will always be any political party’s priority.

I recently made an argument that the great effort by the Conservative Party to recruit more minority MPs, and the greater visibility that the party gives them once in office (in comparison to Labour), for example Priti Patel or Sajid Javid, is a strategy to repair the Party’s nasty image of a ‘white, male and stale’ party not just among the minorities, but also a much larger part of the electorate: white, young, cosmopolitan, educated, centrist Londoners.

The crucial voters the party must win from the Lib-Dems and Labour at each election are as much an audience for the increasing party diversity as are ethnic minority voters. However, this opened the question why Labour, despite their much greater pool of potential minority candidates among their loyal minority voters, seems to be so much more relaxed about having more ethnically diverse MPs and having them take on more visible jobs. Is it that Labour already has the minority vote, reputational advantage and all-round better image? Or is it because as much as ethnic diversity could help Conservatives with winning ex-Labour voters over, it could actually hurt Labour in winning ex-Conservative or, even more prominently, UKIP voters?

For this to be true however, the Conservative Party’s image must benefit from voters being aware that this party is ethnically diverse and among the right kind of voters too: the potential switchers. Also, we should see that Labour’s ethnic diversity does not bring similar benefits as their potential voters- the switchers from other parties- will not reward diversity in their improved image ratings. To see if these conditions hold I asked, in a YouGov survey* from April 2015, nearly five thousand British voters from a nationally representative online sample, what they thought about either Labour and Conservatives.

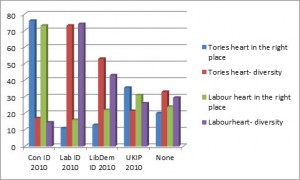

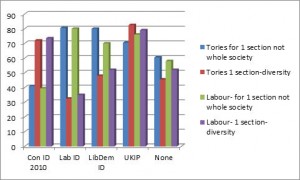

Just before they answered the party-image questions however, some of them were presented with a positively framed sentence about this party’s ethnic diversity, while some of them were not. This single-party design avoided a complication of any comparison between the parties. This manipulation let me see whether respondents who saw diversity information had a more positive opinion of the party they were evaluating than the respondents who were not given this prompt. In the two graphs I show how Labour and Conservatives were perceived by party identifiers of different parties (taken from YouGov’s 2010 records of their respondents’ allegiances) according to whether they heard a positive fact about party diversity or not.

The results are striking. Ethnic diversity affects parties very differently, but mostly as a result of who their target new voter- ie potential switcher- is. So, Labour who must win votes from those who supported Conservatives, UKIP and Lib-Dems in the last election loses out on diversity, because the voters of Conservative party (and to some extent UKIP) punish diversity. Conservatives on the other hand benefit clearly from diversity, since they need to win voters from Labour and Lib-Dems (and to some extend UKIP), and those voters on the whole reward diversity (see Figures 1 and 2 for details).

In fact, the Conservative identifiers punished diversity a lot more than UKIP identifiers did- mostly because the latter were very negative about both the parties regardless of what they thought their ethnic diversity was. The Labour identifiers reacted positively to both their own party and Conservatives’ diversity and so did Liberal Democrat identifiers. Perhaps most importantly for the two main parties, the people who declared no party identity in 2010- the desirable floating voters- also on the whole rewarded diversity (although less than Lib-Dem and Labour identifiers).

It is clear that the strategic, vote winning, considerations lie behind a de-emphasis placed on diversity by Labour, and a great emphasis by the Conservatives. Moreover, this means that the current trends are likely to exacerbate towards the next election. Given that in many seats UKIP are now in second place to Labour, and that the party need to win more Conservative voters at the next election, ethnic diversity is not likely to become the party’s top issue. Similarly, given the need of the Conservatives to win more London seats from Labour, they are likely to pursue the agenda of diversity as strongly as ever.

Figure 1: Labour and Conservative’s party images without and with diversity prompt: ‘Even if I don’t always agree with it, at least its heart is in the right place’. By 2010 party identity.

Figure 2: Labour and Conservative’s party images without and with diversity prompt: ‘It seems to appeal to one section of society rather than to the whole country’. By 2010 party identity.

*Many thanks to Rob Ford who allowed me to use his YouGov survey to carry my questions.

Disclaimer: The views presented in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the research team or those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).