Extremist attacks have escalated in recent weeks – not just in Tunisia. Youths from Dewsbury and High Wycombe have reportedly died as a suicide bomber in Iraq and as a member of Al Shabaab in Kenya. Professor Kate Cooper offers a historian’s perspective on the attraction of violent extremism to idealistic youth.

When young people fall prey to adult handlers, or turn away from parents and teachers who ‘just don’t understand’, it is not always because they do not have strong relationships at home. A consensus is emerging among researchers that while young people’s receptiveness is sometimes rooted in a sense of alienation, a misguided sense of idealism often plays a surprisingly important part.

We think of the problem as characteristic of the internet age, yet – minus the smart phones – it has been repeated cyclically across history. A particularly important insight is the communicative reach – the ‘shareability’ – of stories of the unjust exercise of authority, especially to audiences composed of defiantly idealistic youth. The communicative urgency of this motif simply cannot be overstated, and defusing its power is one of the most urgent tasks in preventing extremism.

I was asked to offer a historical perspective on this issue for a recent exchange between academics and policymakers sponsored by the Mediating Religion Network. The churches and museums of Western Europe are filled with images celebrating the ‘dangerous youth’ of another millennium, the early Christian martyrs. Early Christian literature celebrated the heroic deaths of male, female and child martyrs – moral protagonists remembered as destabilizing the Roman state through acts of courage in the face of attack by unjust authorities.

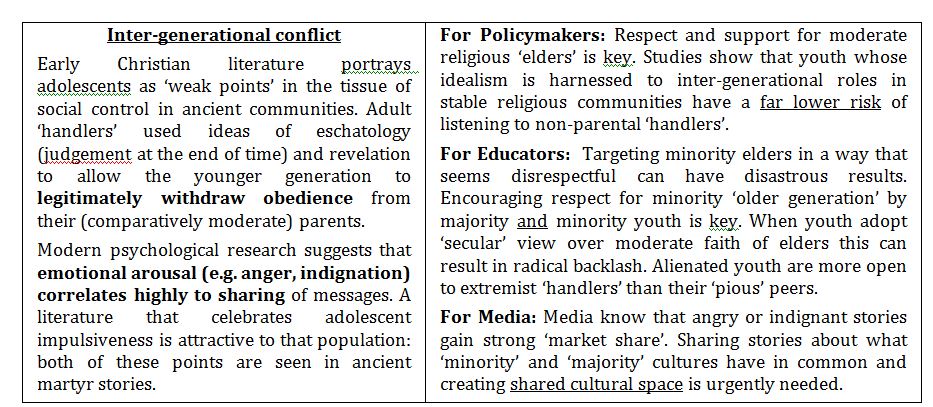

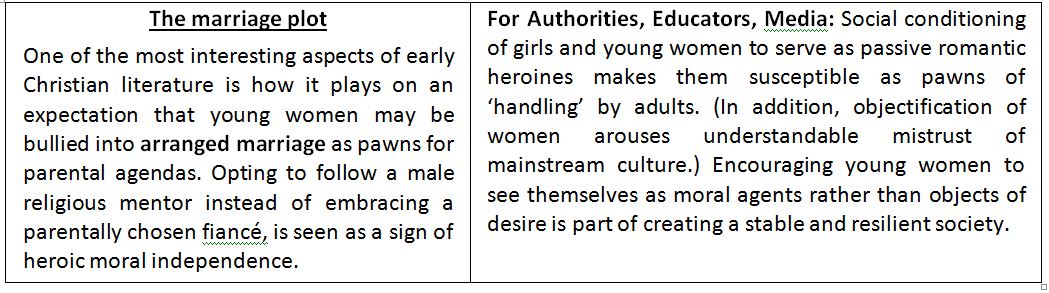

A lively strand of this literature celebrates adolescents who defied their parents in order to follow the Christian apostles. Interestingly, girls were revered with particular affection for choosing death over a parent-sanctioned future of arranged marriage at the urging of radical Christian ‘handlers’ – these are the ‘virgin martyrs’ of Catholic lore.

My research on the Early Christian Martyr Acts has shown that in the decidedly low-tech environment of the later Roman Empire, stories of adolescents who challenged the conformist religion of their parents achieved a viral reach almost unprecedented in the ancient world. Indeed, the stories of these martyrs are still being told in churches around the world today. But it is a mistake to imagine that religion in and of itself is the driving force behind these stories. From Hitler’s Germany to Mao’s China, non-religious ideologies have encouraged radical children to turn against – and even inform on – their more moderate parents.

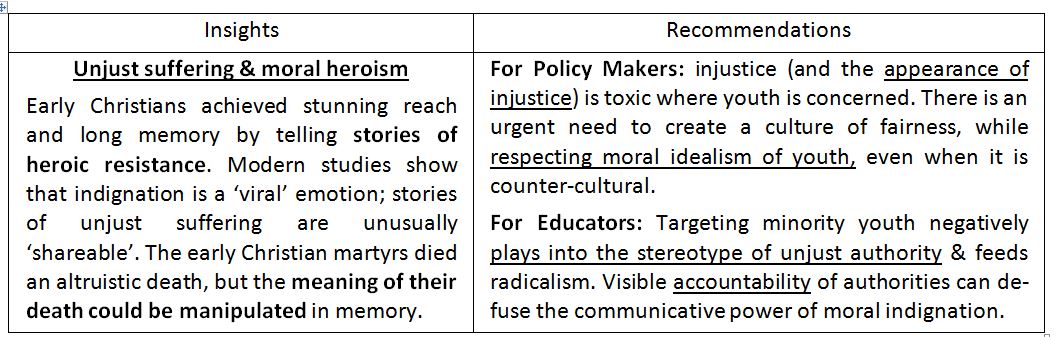

I offer below a telegraphic summary of key insights from the early Christian martyr narratives that may be useful in thinking about identity, idealism, and religious violence where modern adolescents are concerned.

These recommendations draw on research funded by the Leverhulme Trust and R.C.U.K. Partnership for Conflict, Crime & Security Research. See also: Relationships, Resistance, and Religious Change in the Early Christian Household, Martyrdom, Memory, and the “Media Event”: Visionary Writing and Christian Apology in Second-Century Christianity, A Father, a Daughter, and a Procurator: Authority and Resistance in the Prison Memoir of Perpetua of Carthage, and (with project Ph.D James Corke-Webster) Conversion, Conflict, and the Drama of Social Reproduction: Narratives of Filial Resistance in Early Christianity and Modern Britain.