Your likelihood of being offered a place at a Russell Group university may be related to your ethnicity, explains Steven Jones.

Here is an excerpt from a UCAS personal statement written recently by an applicant to a Russell Group university:

“There are various times where I have been a team member such as in hockey, this is where we have to understand our team member’s strengths and weaknesses to evaluate best positions, it makes us understand that one’s ability may be skilful but can always be tackled by two. We had to quickly judge aspects; we also understood how goals and motivation can go through team members, as high motivation can motivate another.”

Some details have been altered to protect the applicant’s identity. However, the writing style is unchanged and captures that of the whole statement.

A natural first response is that the applicant doesn’t belong at a high-prestige institution: the text is poorly punctuated, with muddled content, and reads as though it were thrown together at the last moment. Thank goodness for UCAS personal statements, one might conclude, for allowing universities additional evidence on which to make important selection decisions.

Except things aren’t quite so straightforward.

First, note that this applicant went on to receive A-level grades that were sufficient to gain entry to the courses for which she applied. This suggests that her personal statement difficulties were not caused by a lack of academic ability so much as confusion about what was required. Second, studies like this one, this one and this one, question whether personal statements are really of much value in predicting students’ subsequent performance at university. Third, the applicant was educated in the state sector: evidence suggests that she may therefore have had limited access to the kind of high quality information, advice and guidance available to many of her competitors. And fourth, the applicant is of British-Bangladeshi heritage, a group which fares poorly in admissions to high-prestige universities compared with White applicants of similar academic attainment.

In 2012, I undertook research for the Sutton Trust looking at how university applicants from different backgrounds set about the task of writing their personal statement. My primary focus was on school type, and I discovered that applicants from sixth form colleges and comprehensive schools were much more likely to make basic language errors (spelling mistakes, apostrophe misuse, etc.) than those from grammar schools and independent schools. Workplace experience could also be predicted by school type, with some applicants able to list up to a dozen placements at flash companies, while others struggled to make a Saturday job sound relevant to their chosen course of study.

I’ve since returned to the data to find out whether personal statements also differ according to the ethnicity of the applicant. On average, I discovered, British-Bangladeshi applicants make 2.29 clear linguistic errors per 1,000 words of statement, compared to White applicants’ 1.42 errors. British-Bangladeshi applicants are also low on meaningful work-related activity, averaging 1.57 per statement compared to 2.32 for White applicants. (The total sample size is 327: statements submitted by students achieving identical A-level grades.)

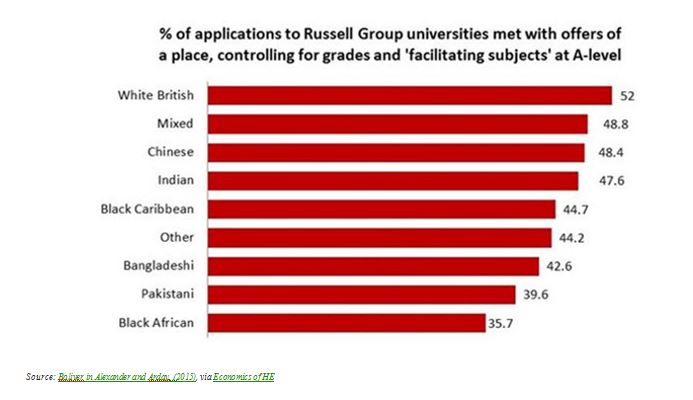

My latest data evaluation was prompted by the graph below, based on UCAS data analysis by Durham University’s Vikki Boliver. This analysis showed that applicants’ chances of getting an offer from a Russell Group university differed markedly according to their ethnicity. British-Bangladeshi students have a 42.6% likelihood; White British students a 52.0% likelihood.

As Parel and Boliver note, ethnicity trumps school type as a predictor of admission to leading UK universities. Figures obtained from Oxford University by the Guardian in 2013 under the Freedom of Information Act indicated that “43% of White students who went on to receive three or more A* grades at A-level got offers, compared with 22.1% of minority students”.

Such differentials can be explained in many ways. Although Boliver’s data controls for ‘facilitating’ subjects (those preferred by universities), it could be that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) applicants take inappropriate combinations for the degree courses to which they apply. It has also been implied that BAME applicants tend toward oversubscribed subjects, such as medicine or law. However, as Boliver points out, the individual-level data needed to develop a clear picture of why differentials arise is increasingly restricted because, supposedly, it “presents a high risk of individuals’ personal details being disclosed”.

Does the application process itself discriminate against some applicants? I’ve written before about how the UCAS personal statement is, in many respects, a flawed indicator, and I’ve responded to arguments made in its defence. Other researchers have noted similar problems with university interviews (see Burke and McManus on would-be Art & Design students who make the mistake of citing hip-hop as an influence, or Zimdars on a tendency for admissions tutors at Oxford University to recruit in their own image).

Such studies raise awkward but crucial questions about what exactly non-academic indicators are supposed to indicate. Is the personal statement simply an “opportunity to tell us about yourself”, as UCAS benignly describes it, or is the real goal to flaunt one’s cultural and social capital, signalling what Bourdieu characterises as the “dispositions to be, and above all to become, ‘one of us’”?

The Observer’s Barbara Ellen notes that certain kinds of applicant are much more likely to “speak uni” and be able to “decode the foreign language of the admissions process.” And Pilkington reminds us that BAME applicants are “entitled to know that they will not be subject to potentially indirect − or indeed direct − discriminatory practices in an institution’s admissions processes.”

However, a key structural barrier seems to be an admissions process that assumes all applicants are equally equipped to understand (and have sufficient support to meet) its veiled requirements. The personal statement purports to help university admission tutors make informed choices based on holistic evidence, but may actually reproduce White and other forms of privilege at the point of application.