As politicians make their final canvasses for the General Election, they will be worrying about voter turnout. Professor Hilary Pilkington and Mark Ellison explain why young adults in the UK are less likely to vote than are their counterparts across Europe.

Thursday’s General Election is widely regarded as the closest and perhaps most important for years. Yet large numbers of younger adults will spurn their opportunity to cast their votes. Why is this and what can politicians do to engage with them?

It is unlikely that young adults will use their votes in anything like the numbers of older adults, nor of their counterparts in elections in other parts of Europe. The MYPLACE project helps to provide some evidence about the reasons.

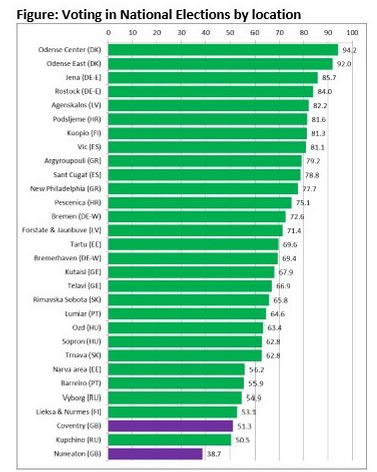

As the table demonstrates, young adults in the two UK locations studied – Coventry and Nuneaton – recorded much lower levels of electoral participation in the last General Election than the MYPLACE study average across Europe.

The proportion of eligible young people voting across the 30 study locations was 70.3%. This is higher than results published by Eurobarometer and the European Social Survey (ESS). But In Coventry just 51.3% of eligible young adults used their votes and in Nuneaton it was a mere 38.7% – the lowest level recorded in the study.

One possible explanation is a cynical attitude towards politics and politicians. The MYPLACE survey asked respondents if they agreed with two propositions: ‘Politicians are corrupt’ and ‘The rich have too much influence over politics’. Answers were combined to create a ‘cynicism’ variable, which were standardised on a 0 to 100 scale, with 100 representing the most cynical.

Young adults in both Coventry and Nuneaton displayed near European average levels of trust in political institutions. The overall average for all locations is 69.2, demonstrating high levels of cynicism towards politicians and politics. Coventry is slightly above the overall average at 69.7, whereas Nuneaton is below the average at 66.1.

However, the countries where young adults have less trust in political institutions than is demonstrated in the two UK locations were mostly in new democracies. It is striking that young adults in the UK exhibit even lower levels of trust than youth in most other established democratic countries.

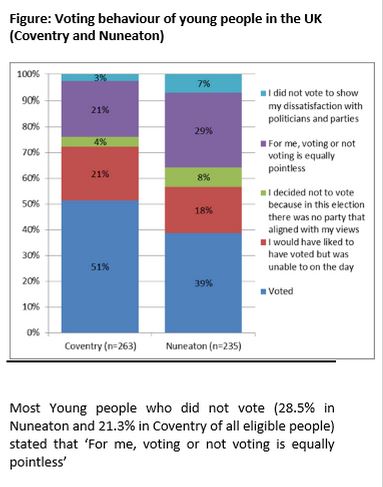

The most common explanation among young adults in Coventry and Nuneaton for not voting was that ‘For me, voting or not voting is equally pointless’. Some 21% of non-voting young adults in Coventry and 29% in Nuneaton expressed this view. There is a widespread sense of the political process having little impact on the way the country is run – and even less scope for an individual vote to prove important.

One interviewee in Nuneaton commented: “No. I don’t, I won’t vote. I know what they say, like oh yeah, they fought to get women’s rights to vote and stuff like that – don’t bother me, does not interest me in the slightest. I don’t, I really don’t find that even if I do vote my vote’s gonna make a difference to who gets what or who does what and stuff like that and what they’re gonna do with it, with that power […] I don’t think it influences it.”

Yet, despite this cynicism, low voting turnout and engagement in non-conventional forms of politics, MYPLACE data appear to confirm that young people continue to attach higher ‘value’ to traditional forms of participation. Scepticism about political institutions does not necessarily mean a withdrawal from all forms of participation. Young adults in Coventry and Nuneaton were more likely than their European counterparts to have volunteered in an election campaign, contacted a politician or local councillor, collected signatures, given a political speech, or distributed leaflets with a political content. (Though the figures in both Coventry and Nuneaton were still low in absolute terms.)

If young people are to exercise their voice in the UK elections on 7th May, they need to be inspired to transform their passive belief in the importance of democratic participation into an active engagement.

Paradoxically, whilst young people in the UK do not appear to exercise their right to vote as much as many of their European counterparts, young people do still state that voting is the most important and effective form of participation.

The challenge facing candidates in this and future General Elections is how to engage with young people in ways that persuade them that casting their vote is an important part of the process of political participation. It would seem that this is no easy task.

Thus while it might appear no easy task for politicians – caricatured regularly as ‘a class apart’ – to engage with young people in ways that enthuse them, they need only look to Denmark – where over 90% of young people in the MYPLACE survey said they had voted in the last national election – or even closer to home in Scotland – where 68% of 16 to 24 year olds voted in the recent referendum – for some indication of what is possible.

The findings of MYPLACE suggest candidates in this and future General Elections should see the door as half open, not half closed.

- MYPLACE – the Memory, Youth, Political Legacy & Civic Engagement project – is financed by the European Union. Its UK base is at the University of Manchester, with the survey element conducted by Manchester Metropolitan University. Fieldwork was conducted in Coventry and Nuneaton between September 2012 and March 2013.