Despite the educational attainment gap between ethnic minority groups and the White British group narrowing, some ethnic minority groups continue to experience inequalities in education, explains Dr Kitty Lymperopoulou, who has contributed to a book on Ethnic identity and inequalities in Britain which has just been published.

Education policy under successive governments in the UK has been characterised by a series of initiatives aimed at improving school performance and raising educational attainment. Targeting resources at disadvantaged groups to reduce inequalities in education was seen as integral in achieving improvements in attainment.

Historically, ethnic minority groups have been disadvantaged in terms of education and there has been an educational gap between ethnic minority groups and White British people. The 2011 Census shows this is no longer the case. In 2011, one in three people from ethnic minority groups had degree level qualifications, compared with one in four White British people.

Meenakshi Parameshwaran and I used data from the last three censuses to examine the extent of ethnic inequalities in education and how these have changed over time. The analysis shows improvements have not been even across ethnic groups. The largest improvements between 1991 and 2011 were for the Indian and Pakistani groups. These groups experienced large increases in those with degree level qualifications (by 27 and 18 percentage points respectively). The increases in the proportion of people with degree level qualifications were more modest for the Bangladeshi and Black African groups (at around 15 and 14 percentage points respectively) while the smallest improvement was for the White group (13 percentage points).

There is no doubt that these improvements reflect wider and better access to higher education, particularly among women. Educational attainment has been increasing among ethnic groups as a result of improvements in access to education overseas. The number of minority ethnic people educated in Britain has also increased. Our analysis of the ethnic group educational gap by age and gender – which is published in the book Ethnic Identity and Inequalities in Britain, released this month – demonstrates these improvements.

The 2011 Census shows that there are large differences in attainment between younger and older members of ethnic minority groups. These differences are greater among ethnic minority women than men, particularly in the Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups. On average, a third of Bangladeshi and Pakistani women had no qualifications in 2011. But the proportion of Bangladeshi and Pakistani women aged 50 or above without qualifications (at 75% and 65% respectively) was more than seven times and six higher than that of Bangladeshi and Pakistani women aged 16 to 24 (10% and 11% respectively).

The gender gap in attainment also seems to have narrowed over time. While Bangladeshi and Pakistani men, on average, had a lower proportion with no qualifications (24% and 21%) compared to women (33% and 30% respectively) in 2011, there was hardly any difference between men and women with no qualifications in the 16 to 24 age group.

Despite these improvements, some groups continue to face a disadvantage in terms of education. In 2011, people from Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups were less likely to have degree level qualifications than White British people (25% and 20%, compared with 26%).

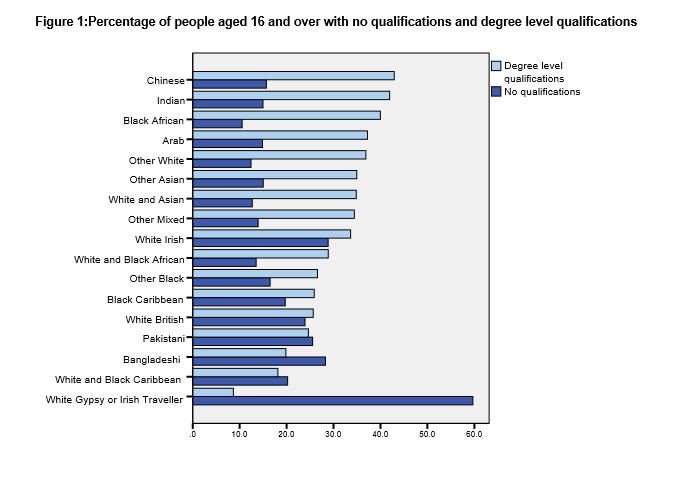

The proportion of people with qualifications was even lower among some other ethnic groups. One in ten people from the White Gypsy and Irish Traveller group had degree level qualifications in 2011, while six in ten were without any qualifications. At the same time Indian, Chinese and Black African groups outperformed all other groups, its members being more than one-and-a-half times more likely to hold degrees than White British people (see figure 1).

The reasons some groups perform better than others may be structural. Some groups may simply have better access to resources than others to enable them to gain qualifications. Targeting resources to address the under-performance of ethnic minority pupils – for example, through the Ethnic Minority Achievement Grant (EMAG) – may have helped raise attainment levels. Some ethnic groups may also value education differently and have higher aspirations than others. Cultural reasons such as practices and expectations about family formation may also explain the lower attainment among women, particularly in the Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups. Geography also plays a role, although our work on local ethnic inequalities shows that ethnic inequalities are widespread across the country.

The positive selection of migrants to the UK has meant that foreign born people are more likely to be highly qualified than UK-born people. The ethnic groups with the highest attainment – Indian, Chinese and Black African groups – all grew mainly through immigration. One in three people born outside the UK in England or Wales had degree level qualifications in 2011, compared with one in four of those born in the UK. Recent arrivals are typically more highly qualified than earlier immigrants and they tend to be younger. This explains the large educational gap by age within ethnic groups.

Despite significant progress, it is clear there remain significant disparities in education between people from different ethnic groups. Although members of ethnic minority communities are better educated than White British people, they remain subject to inequalities in employment. As demonstrated by CoDE research examining ethnic inequalities in the labour market, unemployment remains higher amongst most ethnic minority groups than for the White British. The unemployment rate of the Black African group – one of the most qualified groups in 2011 – was around three times higher than that of the White British group. This suggests that the priorities for policy should not just be about raising the attainment of ethnic groups that are underperforming. Policymakers will need to ensure that better education leads to better jobs. It is clear that ethnic minorities continue to face barriers to upward social mobility. Unless these barriers are removed, ethnic social and economic inequalities will continue to persist.

Source: 2011 Census

- The views expressed in this article are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).