Lifetime experiences of racism damage the health of ethnic minorities from before birth until death, writes Dr Laia Bécares.

Racism is toxic for health. This can be taken literally, proven by a vast environmental justice literature that shows how some ethnic minorities are more likely than the white majority population to live within close proximity to polluting activities, including toxic, hazardous and dangerous waste facilities. It can also be understood metaphorically, since racism is like a poisonous substance that permeates social interactions and structural opportunities and results in persistent inequalities for some ethnic minority groups, compared to the white majority.

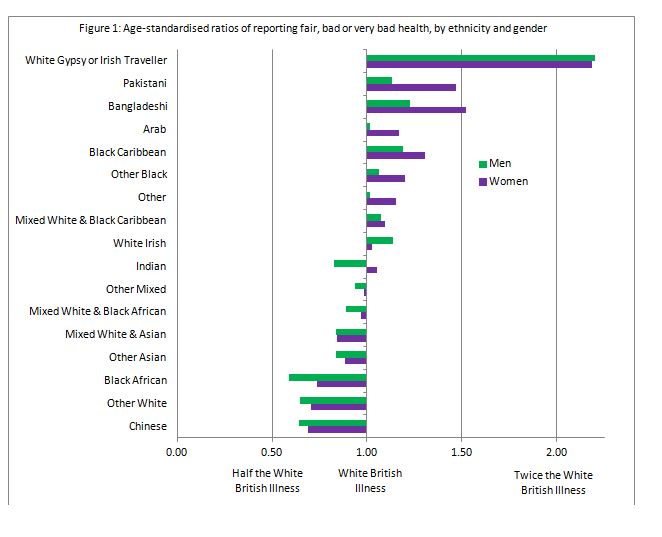

Health is one area where inequalities across ethnic groups become easily apparent. Data from the 2011 Census, presented in Figure 1, show higher rates of reporting poor self-rated health across some ethnic minority men and women, compared to the white British group. White Gypsy or Irish Traveller men and women have by far the highest rates of poor self-rated health, over twice the rate of white British men and women, and higher than all other ethnic minority groups. Other groups such as Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Arab, Black Caribbean and white Irish also have higher rates of poor health than the white British group.

Racism is a well-documented cause of these ethnic inequalities in health. The experience of racism and discrimination is a key contributor to ethnic inequalities in health. This is felt directly – through higher blood pressure and stress, for example. It also has indirect effects through social inequalities that reduce people’s life chances, by leading to poorer housing standards and other factors that damage health and life expectancy.

The harm caused by racism and discrimination to health starts early in life. Studies in the US show that babies of mothers who have been discriminated against are more likely to be born with low birth weights, compared to babies of mothers of similar age and socio-economic standing who have not experienced racism and discrimination.

These findings are relevant to the UK, where Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi and Black Caribbean infants are more likely to have low birth weights than white infants. Low birth weight has implications for health and cognitive function during childhood, adolescence and well into adulthood, which means that as soon as they are born, some ethnic minority children are already at a disadvantage.

The disadvantage caused by racism accumulates through life. Our work shows that children of mothers who experience racism and discrimination have lower cognitive scores than children of mothers who do not report experiencing racism. Nationally representative data from the UK Millennium Cohort Study demonstrates the scale of the problem. Five-year-old ethnic minority children of mothers who in the past year have been racially insulted – or whose family members are frequently treated unfairly because of their ethnicity – score lower on cognitive tests compared to ethnic minority children of the same age and similar socio-economic conditions whose mothers have not experienced racism or discrimination.

We also find that ethnic minority children who live in neighbourhoods where racial insults or attacks are common are more likely to have socio-emotional difficulties and lower cognitive test scores than ethnic minority children with similar socio-demographic characteristics, but who live in less racist neighbourhoods.

These studies illustrate the influence of racism and discrimination in the environments where children are growing up, including in the womb, in the household and neighbourhood. But they do not measure the health consequences of the racism and discrimination that the children experience directly.

There are not any UK-based studies on this issue yet, but studies conducted elsewhere show that children who report they have experienced racism and discrimination are more likely to have anxiety, depression and psychological distress, compared to children who do not report having experienced racism and discrimination. Children who have experienced racism and discrimination are also less likely to have high self-esteem and high self-worth.

These are only a few examples of the burden of racism and discrimination on the health of ethnic minorities from birth to childhood. Further harm is caused by racism and discrimination in adulthood. This is well documented. The impact is felt indirectly through differential access to employment opportunities, good-quality housing and residence in deprived neighbourhoods. All these factors have their effects on life chances and health.

The impact of dealing with disadvantage through the life course – what Arline Geronimus has called the ‘Weathering hypothesis’ – wears down the body’s organs and tissues, particularly the cardiovascular system, causing advanced health deterioration and early death. Recent figures from England show that the disability-free life expectancy at birth for Bangladeshi men and women is 54.3 and 56.5 years, respectively; 7.5 and 7.6 fewer years than for white British men and women. Among the Pakistani group, men have six fewer years of disability-free life expectancy than white British men, while Pakistani women have nine years less disability-free life expectancy than white British women. Black Caribbean, other mixed, Indian, other Asian and other Black groups also have fewer years of disability-free life expectancy at birth than the white British group.

These inequalities in disability-free life expectancy result from the accumulation of disadvantage throughout ethnic minority people’s lives. That disadvantage results from racism and discrimination – and begins before birth.

The views presented here are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of other members of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).