The UK has had a clear dividing line between its political and administrative leadership. In the third post in our series examining the current state of the Civil Service, Professor Colin Talbot argues that the rise of the SPAD and the Tsar is changing this.

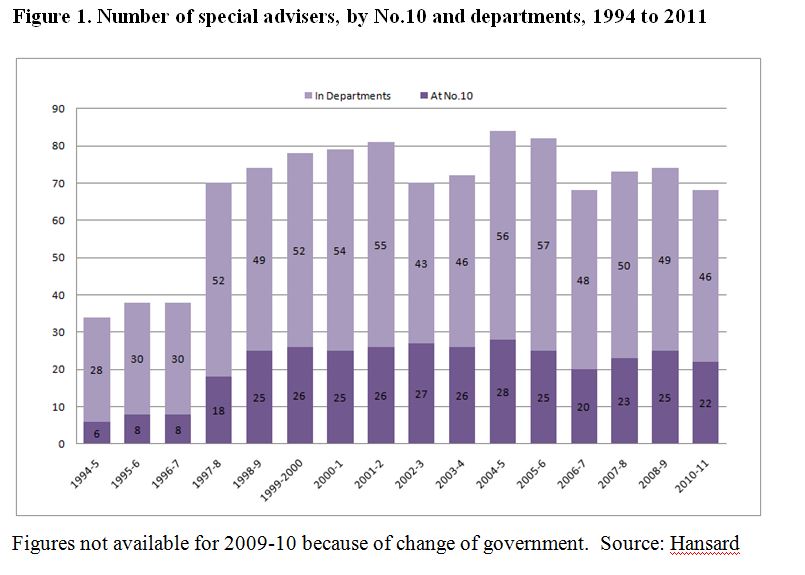

Special advisors – or SPADs, to use their common acronym – operate at the heart of government. While they are not new, they expanded rapidly in number under the New Labour government of 1997 to 2010. And they have continued at similar levels under the current coalition government (see Figure 1).

Alongside the increase in SPADs has been the growth of another, more ambiguous, category – the so-called ‘tsars’. Tsars are appointed by the Prime Minister or ministers to review an area of policy, often for a limited term. The name has been criticised as seeming to imply executive power, rather than the more common actual role of policy advice.

In the first two years of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government more than 90 tsars were appointed to investigate, advise, recommend and even sometimes act on specific policy areas. The previous Labour government appointed around 189 tsars in its 13 years. This suggests tsars are an important new feature of the political-administrative landscape.

Many tsars are not ‘political’ in the sense that SPADs are – they are not necessarily supporters of the parties in power. But they are an alternative source of policy advice to the traditional civil service.

Nor are tsar appointments subject to the same procedures – or accountability mechanisms – applied to SPADs, which have become institutionalised and regulated. There have probably been more than 50 tsars in place at any one time for the whole period since the mid-2000s. (The exact figures are not available.)

For the sake of ease, let’s call this whole class of officials “Politically Appointed Counsellors” or “PACs”. Taken together, PACs (SPADs and tsars) represent a significant shift in the way in which the policy-advice function operates in central government. There are probably today well over 130 SPADs and tsars engaged in policy-advice roles in British central government. Given that there are about 120 ministers in British central government, this means there are 250 or so politicians and politically-appointed policy-makers operating within the core executive.

Compared to the total Senior Civil Service, the political and politically-appointed elite remains small – 250 or so compared to the 4,000 plus in the whole SCS. But that comparison may be misleading. It might be more appropriate to compare the ministers plus PACs with the very top of the civil service – the so-called ‘Top 200’, or the ‘elite of the elite’. This group has arguably equivalent status to the political elite – and is slightly smaller in number.

This raises interesting issues about the real balance of power between the political and administrative elites in government. On this analysis, ministers and politically appointed ‘supporters’ outnumber the senior mandarins, which is not the commonly accepted image. It would be wrong to push this analysis too far – mandarins have the support of the 4,000 plus strong SCS and thousands more who support policy work at every level. Civil servants control the flow of information to ministers, and PACs. Without their co-operation, PACs can not operate effectively. That co-operation can be withdrawn if civil servants perceive PACs not to be fully supported by their ministers, for any other reason in a weak position.

On the political elite ‘side’ of the equation, not all PACs have equivalent status to top civil servants and many tsars are not themselves ‘political’. Nor are ministers and PACs organised into integrated ministerial offices, as in Australia, or ‘cabinets’, as in France.

PACs are also not evenly distributed within government. In the Prime Minister’s office there is a substantial group of PACs. But in individual ministries there are usually only two or three – making them very isolated.

So the balance of power in terms of numbers, knowledge and organisation clearly still lies with the permanent civil service administrative elite. Yet there is no doubt that the political elite has been steadily acquiring greater resources, independent of the civil service. This may be an evolutionary process, but it is changing. Recent moves by the Coalition government, partly as set out in their 2012 Civil Service Reform Plan, suggest there could be an acceleration in this trend.

More recently, the Government decided, after a commissioned report from a think-tank, to inaugurate ‘Extended Ministerial Offices’ and issued guidance to departments on how these should be established. The Civil Service Commission drew up rules for appointments to these new ‘EMOs’. It remains to be seen to what extent these EMOs actually get set up between now and the 2015 General Election, but it is unlikely to be very many – mainly because the complications of coalition government make this initiative very challenging.

This EMO initiative and the increase in SPADs and tsars emphasise the point that the political elite as a whole regards the SCS as a separate entity to be treated with caution, at the very least. The narrative of ‘Yes, Minister’ and ‘Yes, Prime Minister’ was firmly rooted in public ideas about bureaucrats as ‘budget maximisers’, with their own self-regarding motives who will seek to thwart ministers.

The growth of PACs – SPADs and tsars – under governments of all main parties – seems to confirm that this trope still has strong purchase on the thinking of the political elite. Ministers’ desire for alternative sources of support and advice from outside of the civil service suggests a continuing, and even increasing, lack of trust in the administrative elite.