Over the coming weeks Policy@Manchester will run a series of blogs exploring the role of the Civil Service and how it works with Government Ministers. In the first, Colin Talbot explores whether “Sir Humphrey” is no more. Has the Civil Service moved away from the image of the public school, Oxbridge, pale, male and stale image of “yes, Minister”? Superficially, the Senior Civil Service has gone through a major transformation, with more women and ethnic minorities, and fewer former public schoolboys, reaching the top. But, argues Colin, much of the change is skin deep.

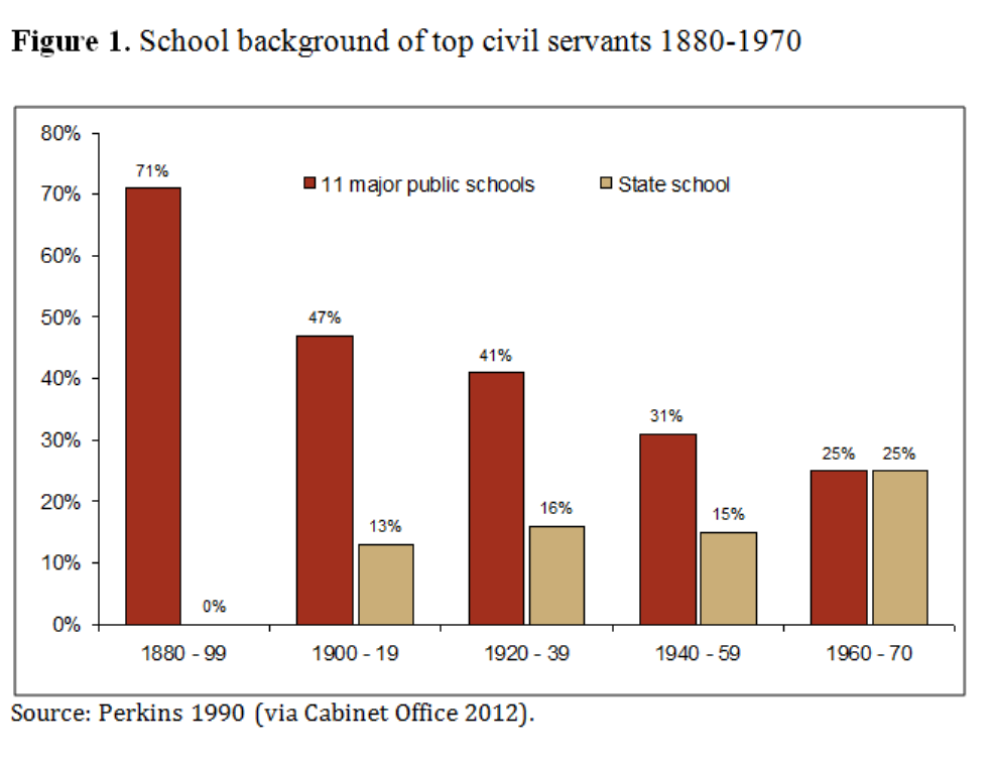

Contrary to its popular image, the Senior Civil Service (SCS) has become less dominated by ‘upper class’ backgrounds than is the case in many other professions. The proportion of ‘public school’ educated top civil servants has declined over the past century (see Figure 1), standing now at only 27% of the ‘Top 200’.

Other British elites remain dominated by the ‘public school’ educated. Of judges, 70% went to ‘public schools’; as did 54% of company CEOs and journalists; 51% of medics; and 42% of scientists and scholars.

The number of SCS Fast Stream entrants from Oxford or Cambridge fell from 34.5% to 26.0% between 1998 and 2011. And the increase in direct entry to the SCS enabled people to join from the private sector, avoiding the traditional Fast Stream route.

Business elites have influenced the SCS in other ways, too. These include secondments into the civil service, especially from the big accountancy firms into HMRC; the use of management consultants; former senior civil servants joining the private sector; and the appointment of ‘non-executive directors’ to the boards of ministries and agencies.

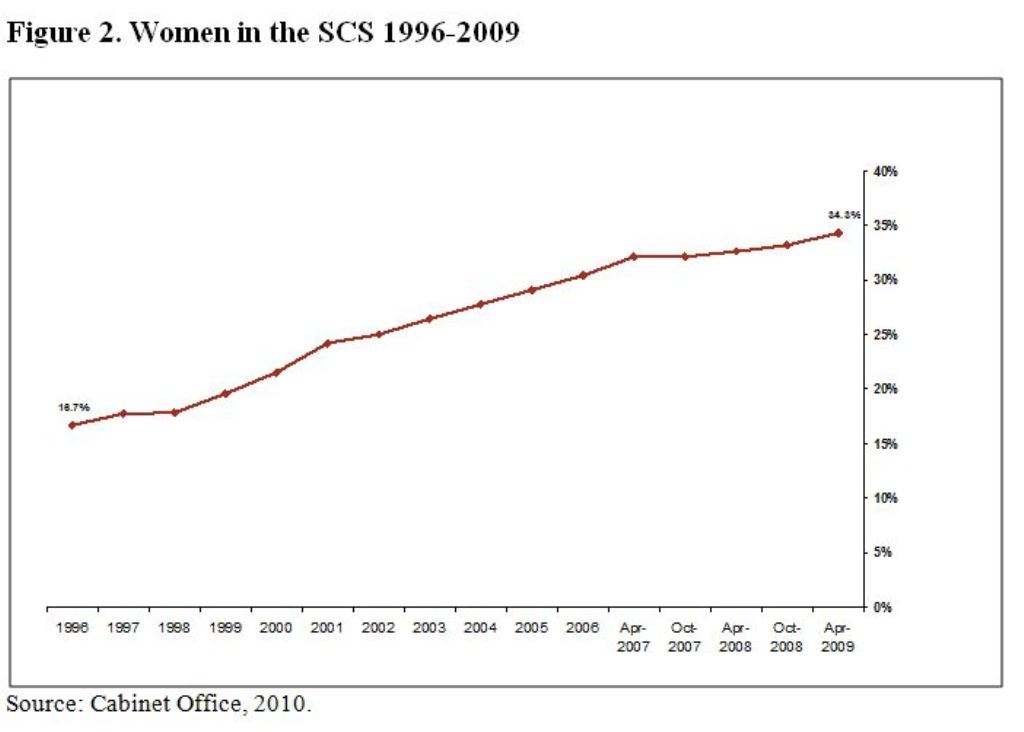

The ‘male and pale’ character of the top civil service has also begun to change –more women are now at senior ranks (see Figure 2). Over a third of the SCS are now women. Ethnic minorities have begun to penetrate both the civil service as a whole (up from 5.8% to 8.9% between 2000 and 2009) and the SCS (at 4%).

The administrative elite is, very slowly, becoming more sociologically representative of British society. How much is owing to specific policies, and how much to general modernisation trends in society and labour markets, is unclear.

Participation of ethnic minorities in the civil service as a whole (8.9%) is almost exactly the same as in the rest of the public service (8.7%) and the private sector (9.1%). Neither for women nor ethnic minorities does participation at the top (34% and 4% respectively) come close to reflecting participation in the whole civil service workforce (53% and 9% respectively).

Yet even in 2011, over 70% of applications for the Fast Stream still came from households with at least one parent in the ‘higher managerial, administrative or professional’ occupational categories. Whilst the extreme elitism of the past may have been modified, the Fast Stream still mainly attracts candidates from an elite social group, albeit a wider one than was traditionally the case.

The increase in external recruitment may also be less significant than it seems. Much of this has been to specialist posts like finance, IT, procurement, human resources, strategy and communications. Likewise, there has been considerable recruitment to ‘operational’ service delivery roles, especially in the ‘Next Steps’ agencies. Most of the core policy functions remain dominated by career, ex-Fast Stream, civil servants.

Meanwhile, the role of the ‘generalist amateur’ has been reinvented as the ‘policy professional’. Traditionally, few senior civil servants had a higher degree. They moved from post to post fairly rapidly, with little regard to experience or expertise. A senior civil servant might be in charge of national roads policy one week and Home Office human resources the next.

Attempts have been made since the Oughton report in 1993 to make the core policy-making function more ‘professional’, establishing clearer career paths. These have included the so-called Northcote and Trevelyan programmes run by the (then) Civil Service College, the Top Management Programme run by the Cabinet Office and the ill-fated Civil Service MBA of the 1990s.

Basic training and experience of the core policy civil servants remained largely unchanged. This may be changing.

In our recent survey of the SCS, of those who answered our question about their qualifications, all had first degrees, over half had a Masters or equivalent and a quarter said they had PhDs. This is probably a biased sample, which is why we did not use it in our report, but it is indicative of possibly important changes taking place within the SCS.

The most recent initiative to get away from the ‘gifted amateur’ image and reality was the Professional Skills for Government (PSG) programme initiated by the last Labour government (abandoned by the 2010 government). PSG sought to ‘stream’ senior civil servants into ‘professions’. One focussed on ‘operational management’. Another was a functional specialist ‘profession’, focussed on finance, IT, purchasing, etc. The third was the ‘policy’ profession, focussed on the policy-making role. Very little seems to have changed as a result of PSG – indeed it cemented many of the traditional features of the ‘gifted amateur’ policy elite into place.

Whilst the sociological composition of the SCS changed somewhat over the years, the SCS culture may not have changed to the same degree. The traditional view of the senior civil servant as a detached, cerebral, cultured, politically neutral and essentially amateur generalist does not require that such people must come from private schools, or Oxbridge, or even be white and male. Anecdotal and observational evidence suggests that the traditional culture at the top has changed much less than the sociological changes would imply.

Few senior civil servants have operational experience of running services within the civil service. More have external experience in the private sector, but their core in-house experience remains drafting policy statements, white papers, legislation and other policy outputs. As the ‘Next Steps’ report of 1988 concluded, most senior civil servants’ attention was firmly focussed upwards on policy-making rather than downwards on policy delivery. This remains true today.