Today’s Autumn Statement by Chancellor George Osborne was both a report card and a manifesto.

It was a (self written) report card on the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition Government that has been in power since May 2010.

But it was also a manifesto for the Conservative-only government George Osborne would like to see after May 2015.

BACK FROM THE BRINK?

The central argument of the ‘report card’ part of the Statement is simple: we came into office facing a crisis: “back then [2010] Britain was on the brink” says Mr Osborne. On the brink of what he doesn’t explain.

As Alistair Darling has recounted in his fascinating book “Back from the Brink”, the real crisis for Britain was not in May 2010 but October 2008, when the British and global banking systems nearly went bust. What we faced in 2010 was the fall-out from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), especially its impact on Government finances.

The crisis of government finances we faced in 2010 was of a different order of magnitude to the GFC of 2008, although it was serious. The governments’ deficit (the gap between income and expenditure in any one year) had leapt from around 2-3% of GDP in 2001-2007 to over 10% in 2008-09 as a consequence.

This was due to several factors. The biggest by far was the slump in the private sector brought on by the GFC. This crashed tax revenues by around 2-3% of GDP, but it also meant that as the private sector shrank public spending appeared to be a much larger percentage of GDP – even though it had mostly remained at the same level as before the GFC.

We also had to bail out the banks – giving guarantees, loans and nationalizing most of RBS (then the biggest bank in the world). In December 2010 the NAO estimated the government had had to borrow £124bn to bail out the banks (more than spending on the whole NHS). Together with the additional deficit, this pushed up UK debt from 40% of GDP in 2007 to 70% by 2010.

So how has Mr Osborne fared in tackling out deficit and debt problem? The answer is not very well at all. His original aim was to eliminate the deficit by 2015. That will not be achieved – the deficit will have reduced – as a percentage of GDP – by only about 50%.

This is more than slightly ironic as the last General Election was fought on the basis of the Conservatives promising to eliminate the deficit by 2015 and Labour promising to halve it. In reality it turns out the Conservative-led government has only managed to achieve what Labour had promised to do. (What Labour would have managed in practice remains, of course, impossible to know).

Moreover at the start of today’s announcement Mr Osborne attempted a little sleight of hand, suggesting things had gotten better since his March Budget. In fact the net public sector borrowing forecast next year (2014-15) and the year after have gotten worse, not better: up by £4.9bn and £7.7bn (OBR Table 1.2). Only from 2016-17 do they very slightly improve on his March forecasts.

As for the deficit (borrowing) so for the total debt – the OBR now forecasts that the total debt will be higher every year until 2018-19 than was forecast in March – by an average of nearly £3bn a year (OBR Table 1.3).

There are reasons for both these changes – some of which are not under the Chancellor’s control – but that did not stop him making a mighty effort to disguise them in todays announcement.

A COALITION OR A TORY STATEMENT

The Autumn Statement was always supposed to be about forecasting the economy and public finances and setting out the Governments’ “fiscal stance” in the run up to the Budget. Since Labour introduced multi-year ‘Spending Reviews’ back in 1998, it’s fair to say these projections have been generally taken a lot more seriously, especially for medium-term policy.

It is important to note two things. First, projections beyond two years out are notoriously hard to get right because of external factors over which governments have little control. But second, and this is crucial, the projections have to be based on policy assumptions about what the Government will be doing in 3, 4 or 5 years times.

This is where today’s statement is so curious. Last night on Newsnight Danny Alexander, the Liberal democrat and Chief Secretary to the Treasury (effectively Oborne’s deputy) admitted that this Autumn Statement would effectively be the last fiscal statement by the Coalition. It makes assumptions about Government policy throughout the next Parliament (2015-20). But which Government policies?

Close examination of both the Chancellor’s statement and the OBR’s projections suggest that they are based on a Conservative Government.

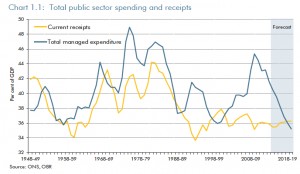

The very first chart in the OBR’s report is based on assumptions about cuts to public services and welfare spending (and no substantial tax rises) throughout the next Parliament:

These cuts would take UK public spending down to levels not seen since the 1930s – not much above a third of GDP (making us more like the United States than Europe). This sort of shift in public spending has been a dream of the Tory right for years, but it was never mainstream Tory policy, much less Liberal Democrat aim. Yet now both parties appeared signed up to it.

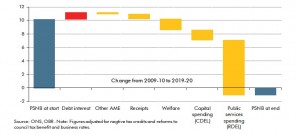

Or take a look, for example, at Chart 4.9 in the OBR’s Report that shows “sources of deficit reduction” (as a percentage of GDP) up until 2020:

This makes clear assumptions about the scale of welfare and especially public services spending cuts that I am pretty sure would horrify most Liberal Democrats. Yet their leadership has effectively signed up to the policies these assumptions are based on. At the very least they haven’t used this opportunity to distance themselves from them.

BALANCED BUDGET BRITAIN?

This brings me to my final point – when did all three of Britain’s main political parties apparently become signed up to a balanced budget?

The idea of a ‘balanced budget’ has long been a shibboleth of the US right, but it has rarely been on the agenda in Britain since the Great Crash in the 1930s. Yet suddenly all three parties seem signed up to it – with minor variations in their stance – without any political debate about its merits

Interestingly, the OBR Chart 1.1 above shows that throughout the post-World War 2 period Briatin has run a deficit of about 2.5% of GDP without too much problem. Only for three short periods did we have a balanced or surplus budget. Interestingly, this is the sort of figure most analysts would tell you is perfectly manageable in a growing, mildly inflationary, economy. So why has it suddenly become so imperative to get it down to 0%? At the very least, we are owed an explanation from our political leaders?