Despite Race Acts intended to ensure equality of opportunity, employment inequality persists – and got worse in each recent recession, explains Professor Yaojun Li.

Ethnic minority men are more likely than white men to be jobless when the economy is booming. During periods of recession they suffer disproportionately higher unemployment rates.

Social surveys covering the last 40 years reveal details of how the labour market operates that are not fully captured by the Census. In particular, Census data does not tell us enough about the impact of recessions. Social surveys reveal the extent to which recessions worsen underlying ethnic minority disadvantages in the labour market.

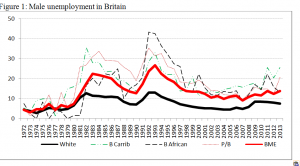

The data in Figure 1 are drawn from the General Household Survey and the Labour Force Survey: these are the most authoritative sources for studying labour market participation. The thick lines represent the unemployment rates for ethnic minority and white men respectively. The thin lines represent the rates for black Caribbean, black African and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men.

At the peak of the recession from the early to mid-1980s, around 13% of white men were unemployed, while the rate for ethnic minority men was 22%. At the peak of the next recession (1992-1993), the rate for white men was again just over 20%, but for ethnic minority men it rose to 27%.

The extent of ethnic minority disadvantaged narrowed in the most recent recession, but did not disappear. In 2013, white male unemployment was 7.5%, while that for ethnic minority men was 13.8%. During a recession, ethnic minority men are about twice as likely to be unemployed as are white men.

In addition, unemployment rates remain higher for longer amongst ethnic minority men than for white men. In both the 1980s and 1990s recessions, unemployment for ethnic minority men fell more slowly for ethnic minority men than for white men. In the most recent recession, there has been a divergence in the fortunes of white and ethnic minority men: unemployment began falling for white men, while still rising for ethnic minority men. Hardships inflicted by the recessions have not been shared equally.

Black Caribbean men arrived in Britain mainly in the 1950s and 1960s to work in London Transport and in other skilled or semi-skilled manual jobs. They were the ‘first to go’ when large-scale unemployment began. Between 1979 and 1980, when white men’s unemployment rates rose to 6.5%, black Caribbean men’s rates were already at 16%. In 1982, nearly one in eight white men was unemployed, compared to one in three black Caribbean men.

Pakistani/Bangladeshi men were affected similarly, as large numbers were employed in textile factories, many of which closed. Unemployment rates for Pakistani/Bangladeshi men stayed two to three times higher than for white men thereafter.

By the time of the 1980s recession, black African men in the UK had been ‘positively selected’, to use the language of economists. That is to say, they were mainly people who had arrived to study in the UK, stayed on, and were highly educated. Even so, black African men were nearly twice as likely to be unemployed as white men during the 1980s recession.

The patterns for the 1990s recession are especially disturbing. In the period 1992 to 1993, white male unemployment rates rose by around 4%. But those for black African men increased by 23%. In 1997, white male unemployment fell back to its 1978 level. But the rate for black African men remained very high.

Although our data could have some sampling errors, we can be confident in concluding that since the early 1980s, black and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men have been generally twice as likely to be unemployed as white men. During the peak of the recessions, that disparity rose to the extent that black and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men were three times more likely to be unemployed. The Census micro-data for 1991, 2001, and 2011 fails to capture the most serious recession effects.

These negative impacts on ethnic minorities are even worse for young people during a recession. Around one in five white young men was unemployed during the recessions of the 1980s, 1990s and 2009 onward. The rates for black young men were much higher at 36% in 1982, 50% in 1992 and 43% in 2012. The figures for Pakistani/Bangladeshi young men were 34%, 44% and 35% respectively.

There are various demographic differences between the ethnic minority and white populations. Some 56% of the ethnic minority population was born abroad, which may have caused educational disadvantage. But even if we compare the majority and minority groups with the same age, education, marital status, health condition, geography and family situation, we still find that black and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men’s unemployment rates are two to three times higher. This kind of net difference is what sociologists call the ‘ethnic penalty’. There is no clear sign that this is improving.

White Irish men were more likely to be unemployed than white British men up to the 1990s, but there was little difference thereafter. White men from the old Commonwealth countries and Europe did not have higher rates of unemployment than did white British men in the four decades considered here. Indian men were more likely to be unemployed than white men up to the mid-1990s, but there was no difference thereafter. Unemployment amongst Chinese men was generally similar to that of white men.

Overall, ethnic minority men of black and Pakistani/Bangladeshi heritages had high unemployment rates and were hardest hit during recessions. Recessions come and go, but there is little change in the underlying fortunes, or misfortunes, of some ethnic minorities. There is a long way to go before true equality of opportunity is reached for male employment.

- The views presented here are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect those of other members of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).