This is the fortieth in a series of posts by Dr Robert Ford, Dr Will Jennings, Dr Mark Pickup and Prof Christopher Wlezien that report on the state of the parties in the UK as measured by opinion polls. By pooling together all the available polling evidence, the impact of the random variation that each individual survey inevitably produces can be reduced.

Most of the short term advances and setbacks in party polling fortunes are nothing more than random noise; the underlying trends – in which the authors are interested and which best assess the parties’ standings – are relatively stable and little influenced by day-to-day events. If there can ever be a definitive assessment of the parties’ standings, this is it. Further details of the method used to build these estimates of public opinion can be found here.

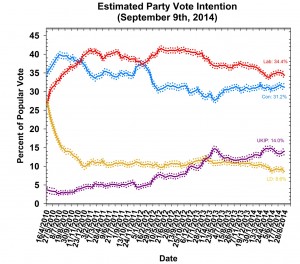

While last month’s Polling Observatory saw UKIP fall and the big two rebound, this month sees the opposite. Once again, rumours of “peak UKIP” look premature – our model puts Farage’s party at 14.0% at the start of September, close to their all-time high earlier this summer.

With a thumping by-election victory looking likely for UKIP defector Douglas Carswell in October, UKIP look set to continue causing headaches in Westminster after the dust settles in Scotland. The Conservatives and Labour both give up last month’s gains, putting them back where they were at the start of the summer.

Our estimates put Labour at 34.4%, a fall of 0.9 points from last month’s figure while the Conservatives close the summer on 31.2%, down 0.8 points. The Liberal Democrats, by contrast, continue to wilt. They are down to 8.6% in this month’s estimates, a drop of 0.2 points and a new all-time low for this Parliament. With seven months to go, Nick Clegg and his colleagues are staring into the electoral abyss. They will have to lean heavily on local incumbency bonuses and anti-Conservative strategic voting to save them from disaster next May.

As we have noted before, the polls in this Parliament seem to have followed a “punctuated equilibrium” pattern, with short periods of intense change followed by long periods of stasis when public opinion settles down into a new pattern. The polls currently seem to be in another of these periods of stasis.

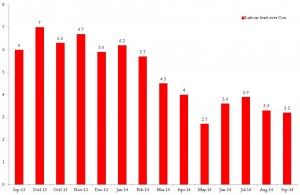

Our chart below shows the estimated leads in the polls for Labour over the Conservatives over the last year. This can be split into three periods. During the final months of 2013, the Labour lead was steady, then fell sharply between February and May 2014, before recovering slightly and leveling off at around three to four points over the rest of the summer.

There are two lessons for poll-watchers from this chart. Firstly, the sharp drop in the spring shows that, with eight months to go, everything is still to play for. Recent Conservative lamentations about the death of their electoral prospects following Douglas Carswell’s defection look overstated. Labour’s lead dropped nearly four points in the course of four months last spring – if this happened again early in 2015 the Conservatives would be ahead in the polls as election day loomed.

Secondly, while there is time left on the clock, it is running out fast. Biases built into the electoral system mean the Conservatives need a lead of several points in the vote to be sure of a lead in seats. Back in May, a shift from Labour to Conservative of 0.5 points a month would have been enough to deliver a three point vote lead and probable seat lead by election day. Four months of stasis in the polls has raised that to 0.7 points a month, and each additional month raises the required slope still further. Time is running out fast for the Conservatives.

Chart: Labour lead over Conservative since September 2013

There are still plenty of things, predictable and unpredictable, that could shift public opinion out of its current equilibrium. The first – and most important – comes next week when Scots vote on whether to dissolve their 300 year old union with Britain. A yes vote upends all the existing political and electoral calculus. Scotland leans quite strongly to Labour in Westminster voting, and even more so in Westminster seats.

Labour would lose 41 seats if Scotland becomes independent, while the Liberal Democrats would lose 11. The Conservatives’ position, by contrast, is barely changed. As one pundit quipped: “what do the Clacton by-election and the Scottish independence referendum have in common? They both cost the Conservatives one seat.”

The Conservatives would have a majority in the current House of Commons without Scotland, and would find a victory on seats – if not an outright majority – much easier in the next election if Scots MPs were excluded. However, Scots would not be leaving the union immediately, which could produce some tricky constitutional situations.

Who governs if the 2015 election delivers a Labour majority with Scottish MPs but a Conservative plurality without them? If things go Alex Salmond’s way next Thursday, this is one of many questions we will all have to consider.