As explained in the inaugural election forecast, up until May next year the Polling Observatory team will be producing a long term forecast for the 2015 General Election, using methods first applied ahead of the 2010 election (and which are also well-established in the United States). The authors’ method involves trying to make the best use of past polling evidence as a guide to forecast the likeliest support levels for each party in next May’s election, based on current polling, and then using these support levels to estimate the parties’ chances of winning each seat in the Parliament. A seat-based element will be added to this forecast at a later date.

This month’s Polling Observatory saw a slight rebound in support for Labour, despite the sustained, now rather tedious, debate over Ed Miliband’s leadership credentials.

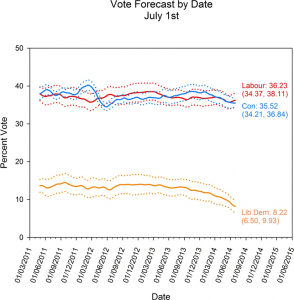

Our forecast, which builds on the historical polling record alone to project forwards to next year’s general election, again puts Labour and the Conservatives in a statistical dead heat, although Labour has edged up to 36.2% and the Conservatives have fallen back slightly to 35.5%.

This Labour lead of 0.7% is far too small to be statistically meaningful at this stage, with polls still providing a very uncertain guide to the outcome. This movement reflects the fact that Labour are holding their support, where the historical record suggests we should be expecting declines at this point.

In contrast, the forecast for the Conservatives is on a downward slope, indicating that they are not making the gains that history would typically expect. Our colleague Steven Fisher has found similar trends in his model, which also builds on historical polling data. If the current poll lead continues into the autumn, the Conservatives may well need to start worrying – the accuracy of polling as a predictor of the general election outcome steadily increases as we enter the last six months.

There is also bad news for the Liberal Democrats, who our forecast puts on 8.2%. Once we introduce the seats-based element to our model, the picture might not look quite so catastrophic for them, but our current expectation is for an extremely poor performance.

Today, all the main parties are struggling to attract the level of support that would indicate a strong prospect of securing a parliamentary majority in 2015. The two-party share of the vote by Conservatives and Labour is as low as it has ever been. All three of the established parties are still running below their historical averages, in part due to the rise in UKIP which has taken “none of the above” vote intentions to record highs.

The relative stasis in the polls is partly because the structural weaknesses of parties and leaders (Miliband’s poor ratings, the damaged Tory brand, and the Liberal Democrat betrayal) are all priced in to the polling numbers we have been seeing. This means that axioms such as that ‘oppositions need to be further ahead at this stage’ or that ‘governments will always be rewarded for a growing economy’ may not necessarily come to fruition given the listlessness of the polls.

It is dangerous to assume that these sorts of factors will always lead to late shifts in opinion. Though there have often been late swings in opinion away from the opposition, or towards the government, this is a tendency not an iron law, as our table below reveals.

| Election year | Govt change last 12 months | Opposition change last 12 months | Swing from opposition to government last 12 months |

| 1955 (CON) | 4.5 | -0.3 | 2.4 |

| 1959 (CON) | 2.1 | 4.7 | -1.3 |

| 1964 (CON) | 4.9 | -0.9 | 2.9 |

| 1966 (LAB) | 3.7 | -1.4 | 2.6 |

| 1970 (LAB) | 13.9 | -8.5 | 11.2 |

| Feb 1974 (CON) | 2.6 | -8.4 | 5.5 |

| 1979 (LAB) | -7.1 | 0.9 | -4.0 |

| 1983 (CON) | -2.6 | 0.5 | -1.6 |

| 1987 (CON) | 10.4 | -5.4 | 7.9 |

| 1992 (CON) | -3.0 | -1.3 | -0.9 |

| 1997 (CON) | 2.1 | -3.3 | 2.7 |

| 2001 (LAB) | 1.1 | -3.5 | 2.3 |

| 2005 (LAB) | 3.0 | -3.6 | 3.3 |

| 2010 (LAB) | 6.6 | -3.4 | 5.0 |

| Average since 1955 | 3.0 | -2.4 | 2.7 |

Our table, built from our polling historical database, shows how the polls move in the last year of a Parliament in each election cycle since 1955. There is a “swing back” tendency towards the government – on average the governing party picks up three percentage points in the last year, and the opposition loses 2.4 points.

But there is a lot of variation around this mean. In some elections, such as 1987 and 1970 there is a dramatic swing back to the government (though note that, on these occasions, the sharp rise in government popularity may have helped trigger the election in the first place, something now impossible with fixed term parliaments). On other occasions, such as 1979 and 1992, the polls record a swing away from the government in the last year. So while an improvement in the Conservatives’ relative position is historically likely, it is not certain, and it is unlikely to be a dramatic shift.

This matters, because the current biases in the electoral system mean the Conservatives need a substantial lead to become the largest party in Parliament, and a hefty one to have any chance of a majority. If the swing back to Cameron’s party is in line with the historical average of 2.7 points, then we would expect the Conservatives to go into next year’s election with a lead of less than two percentage points, definitely not enough for a majority, and probably not even enough to be the largest party in Parliament (particularly if the Liberal Democrats hold up better in seats they are contesting with the Conservatives).

A polling swing back would provide the Conservatives with a valuable morale boost, but thanks to the disadvantages of the electoral system, Cameron’s party still have a lot to do even if the tide of public opinion starts to turn in their favour.