Despite government programmes to address high levels of unemployment in ethnic minority groups, inequalities persist, explains Professor James Nazroo.

The impact of the economic crisis on members of ethnic minority groups has been strangely overlooked. Discussions of falls in unemployment rates and how these relate to part time and insecure – zero hours – employment, have made no reference to how the economic crisis may have had a more damaging effect on people in ethnic minority groups.

While ethnicity and race are commonly no longer considered to be drivers of disadvantage, in fact, ethnic minority groups in England and Wales have a history of lower rates of employment and higher rates of unemployment than the White majority population.

The Department for Work and Pensions has put in place policies to address these inequalities through initiatives such as Ethnic Minority Outreach, Specialist Employment Advisers and Partners Outreach for Ethnic Minorities, and most recently with the establishment of the Ethnic Minority Employment Stakeholder Group. But the individual successes of these initiatives have not led to fundamental changes in labour market inequalities – which is perhaps not surprising given their limited ambition.

A detailed picture of how the relationship between ethnicity and labour market participation has evolved is available from the last three Censuses, covering the period 1991-2011, and our research shows that labour market inequalities have persisted for many ethnic minority groups.

For example, over the period 1991 to 2011, White men had a consistently higher rate of labour market participation compared with men in other ethnic groups, with the exception of Indian men. And the most recent Census shows that in 2011 while over 90% of 25 to 49 year old men were economically active (working or actively looking for work) in the Indian, White British, White Irish and Other White ethnic groups, the equivalent figure was less than 70% for Arab and White Gypsy or Irish Traveller men.

In 2011, there were also large differences across ethnic groups in rates of unemployment. Among economically active 25 to 49 year old men, rates were especially high for the Other Black group (one in five unemployed), Black African, White Gypsy or Irish Traveller, Black Caribbean and Mixed White & Black Caribbean groups (1 in 6 unemployed), when compared with White British men (only 1 in 17 unemployed).

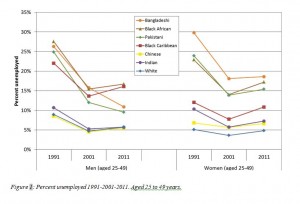

Between 1991 and 2001, unemployment rates for men in this age group decreased for all ethnic groups and there was little change between 2001 and 2011. This shift in unemployment rates left the relatively high rate of unemployment for Black Caribbean and Black African men unchanged, but reduced the disadvantage of Pakistani and Bangladeshi men relative to White men (from three times higher to about one and a half times higher). However, for both of these ethnic groups this was largely a consequence of increases in part-time employment and the higher rates of unemployment remained.

Among women in the 25 to 49 age group, rates of unemployment were very high in the Bangladeshi, Arab and White Gypsy or Irish Traveller groups (one in five unemployed), compared with White British women (one in 21 unemployed).

Between 1991 and 2011, unemployment rates decreased by one quarter for the Black African group; by around one third for the Indian and the Pakistani group; and by almost two fifths for the Bangladeshi group. These large falls in unemployment, compared with a very small fall for White women, led to a decrease in the relative unemployment disadvantage for these women.

However, although the unemployment gap between ethnic groups has narrowed, the disadvantage for many ethnic groups remained large. For Black Caribbean women it has remained consistently high at just over twice the rate for White women.

Indeed, where we have seen reductions in ethnic inequalities in unemployment these have in large part been driven by increasing levels of part-time employment in ethnic minority groups. Overall, men were much more likely to be working part-time in 2011 compared with 1991 figures.

The largest increase in part-time employment was seen for Bangladeshi men (an increase from just over 3% to 35%), meaning that Bangladeshi men were seven times more likely to be in part time employment compared with White men. For women, all ethnic minority women saw an increase in part-time employment between 1991 and 2011 while, in contrast, the rate for White women reduced.

The largest increase in part-time employment was seen for Bangladeshi men (an increase from just over 3% to 35%), meaning that Bangladeshi men were seven times more likely to be in part time employment compared with White men. For women, all ethnic minority women saw an increase in part-time employment between 1991 and 2011 while, in contrast, the rate for White women reduced.

So, ethnic inequalities in labour market participation have persisted. Many ethnic minority groups still have higher unemployment rates and lower rates of economic activity compared with the White majority group.

Why do we continue to see such disadvantage for ethnic minority groups? And why have the media and politicians remained silent on this throughout the current economic crisis?

- The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).