There is economic vibrancy in Asian-dominated areas of the UK, driven by the entrepreneurial spirit of the self-employed, according to some reports. But, says Ken Clark, analysis of official statistics reveals a rather less rosy picture.

Asian-dominated areas of the UK are booming, according to The Economist – in stark contrast to “struggling white towns”. The credit for this boom is given to the entrepreneurialism of the Pakistani community. Citing the fact that Pakistani businesses often seek finance from non-bank sources such as family or through community links, The Economist argues that Pakistani businesses have been shielded from the worst of the financial crisis.

The picture painted is one of a successful, dynamic, booming area and community. But analysing the key Census data reveals a much less rosy picture of Pakistani self-employment in the UK.

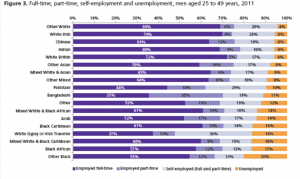

High self-employment rates for ethnic minorities have been a feature of the UK labour market for some time. The figure below is based on 2011 Census data and is taken from the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity’s (CoDE) Census Briefing “Ethnic Inequalities in Labour Market Participation”.

It shows what economically active prime age men (24 to 49 years) were doing in Census week and is broken down into detailed ethnic groups. With the exception of the White Gypsy or Irish Traveller group, Pakistanis had the highest proportion in self-employment. This was also much higher than the other non-white ethnic groups, including those who have traditionally been thought of as being heavily engaged in self-employment such as the Indian, Chinese and Bangladeshi groups.

Two main explanations have been put forward for high rates of ethnic self-employment: one is that ethnic minority workers are pushed into self-employment as a result of limited opportunities or direct racial discrimination in the paid labour market; the other is that ethnic or group-specific characteristics such as a comparative advantage in the production of ethnic goods or a cultural predisposition towards entrepreneurship pull minority individuals towards this kind of employment.

In previous work (here and here), Steve Drinkwater and I have shown that both push and pull factors are potentially important.

For example, we estimated that increases in the wage differential between whites and non-whites in the paid labour market could significantly increase the non-white self-employment rate and that members of certain religions favoured entrepreneurship. However, we found little evidence that “enclaves” of co-ethnic workers or customers boosted ethnic self-employment rates.

Generally the push factor is thought of as a negative reason for entering self-employment, whereas the pull factors may reflect a more positive motivation and a more genuinely “entrepreneurial” form of activity. Both the welfare of the ethnic groups concerned and the wider implications for productivity and growth depend on exactly what those who classify themselves as self-employed are doing.

The overall self-employment rate (the proportion of all in employment classed as self-employed) has been slowly increasing since 2000. And more recently an Office for National Statistics (ONS) report noted the very substantial rise in self-employment jobs since the financial crisis with the economy adding 367,000 workers classed in this way between 2008 and 2012.

Commentators have argued, however, that the rise in self-employment rates seen during the recession should not be taken as a sign of a healthy entrepreneurship but rather as a reflection of the difficulties of obtaining paid jobs and as a contributory factor to the UK’s declining productivity. The fact that the self-employed also tend to work longer than their employee counterparts for lower pay supports this view that push factors are more important (see the links here and here).

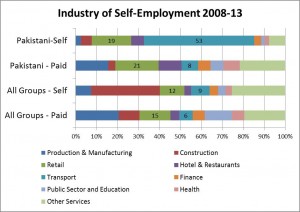

What then of the Pakistanis? Their self-employment rate has also been gradually increasing since 2000 and it is interesting to look at the breakdown of their self-employment into different types of activity. This is done in the figure below which uses data from the Labour Force Survey. The broad industry in which employees and the self-employed work is graphed both for Pakistanis and for all workers. The time period is 2008-2013 and men and women of working age are included.

It is clear that Pakistani self-employment is quite different both to paid-employment amongst that community and to self-employment more generally. In fact, the distribution across industries of Pakistani employees is reasonably similar to that for all workers albeit with more in retail and a lower proportion in production industries and construction.

Amongst the Pakistani self-employed, the predominance of the transport sector is evident with 53% of workers classified in this industry. A more detailed look at the data suggests that this is nearly all taxi driving. Most taxi drivers in the UK are nominally self-employed and essentially offer their services to taxi companies as sub-contractors paying a fee to rent equipment, including radios and sometimes cars, from the company. Long hours of work are common and pensions, sick pay and paid holidays rare. While the nature of the work may offer some flexibility, this is nothing like entrepreneurship in the classic sense.

It’s true that amongst Pakistani self-employed workers a higher proportion (19%) work in retail compared to all ethnic groups (12%) however this has fallen since the financial crisis. In the period 2001-2007, around 24% of the Pakistani self-employed were in retail. Furthermore the proportion in transport has risen from a 2001-2007 figure of 50%. There is little evidence of a burgeoning retail boom here.

None of this is to gainsay the undoubted vibrancy of some Asian high streets identified in The Economist’s article.

But we need to put this into context using nationally representative data. Our analysis, together with ONS estimates that the Pakistani unemployment rate in 2013 was more than double that for all workers, suggests a much less optimistic picture.