This is the thirty-second in a series of posts that report on the state of the parties as measured by opinion polls. By pooling together all the available polling evidence we can reduce the impact of the random variation each individual survey inevitably produces. Most of the short term advances and setbacks in party polling fortunes are nothing more than random noise; the underlying trends – in which we are interested and which best assess the parties’ standings – are relatively stable and little influenced by day-to-day events. If there can ever be a definitive assessment of the parties’ standings, this is it. Further details of the method we use to build our estimates of public opinion can be found here.

January has been a stormy month in and out of politics. While freak storms have dominated the news agenda, politicos have been more excited by freak polls. Conservative activists took the airwaves and the internet to trumpet a YouGov poll showing Labour’s lead over their party down to 2%, only to be beaten back by Labour activists touting another poll by the same company, just days later, showing the Labour lead back into double digits. The reactions such polls garner are a powerful demonstration of the effect of selective, partisan attention – an outlier poll showing the gap between the parties disappearing or yawning wider than it has for many months, is widely quoted, touted and debated. The many other more mundane readings of public opinion receive little attention. The casual reader is left with the impression that public opinion is chaotic, and everything is up for grabs.

January has been a stormy month in and out of politics. While freak storms have dominated the news agenda, politicos have been more excited by freak polls. Conservative activists took the airwaves and the internet to trumpet a YouGov poll showing Labour’s lead over their party down to 2%, only to be beaten back by Labour activists touting another poll by the same company, just days later, showing the Labour lead back into double digits. The reactions such polls garner are a powerful demonstration of the effect of selective, partisan attention – an outlier poll showing the gap between the parties disappearing or yawning wider than it has for many months, is widely quoted, touted and debated. The many other more mundane readings of public opinion receive little attention. The casual reader is left with the impression that public opinion is chaotic, and everything is up for grabs.

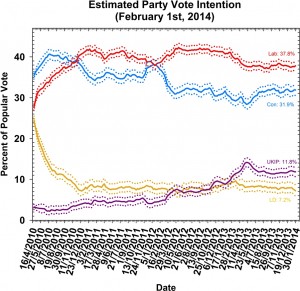

Yet, once we put all the data together, those noisy, attention seeking outliers no longer drive the story. The dull reality this month, as in most months of this parliament, is that public opinion hasn’t moved at all. We estimate Labour this month at 37.8%, up 0.2% on last month. The Conservatives come in at 31.9%, up 0.9% on last month, but merely a return to their steady position in the autumn after a brief Christmas downtick. UKIP stand at 11.8%, down 0.3% on the month, while we estimate the Lib Dems at 7.2%, down 0.6% on last month, one of their weaker showings but not yet evidence of any sustained decline on their long run equilibrium.

While commentators paid to follow the torrent of current affairs full time tend to read meaning into every minor tremor in the polls, in reality public opinion moves slowly, and seldom. The current deadlock in public opinion – with Labour steady in the high thirties, the Conservatives in the low thirties, UKIP around 10-13% and the Lib Dems a little behind them, is by our count the sixth phase in the evolution of the parties’ standing with the electorate over the course of this Parliament. The story to date has run like this:

Phase 1. May 2010 to December 2010: The Conservatives share is high and steady in the initial Coalition honeymoon period, while left-leaning Liberal Democrats angered by their party’s alliance with the Conservatives depart for Labour in droves. Lib Dem support falls, and Labour’s rises, throughout this period. The cumulative swing in support during this period was very large – 12 points or more – sufficient to put Labour ahead of the Conservatives within a year of their worst defeat for a generation. The Liberal Democrats slump to below 10 percent by the end of this period, and has remained steady at 8-10 points ever since.

Phase 2. January 2011 to November 2011: A slow decline in Conservative fortunes as the economy stagnates and the public sours on austerity spending cuts. Labour’s revival stalls as they run out of left of centre Lib Dems to recruit and prove unable to win over disaffected Conservatives. UKIP support begins ticking steadily up in the period, but remains largely below the media radar.

Phase 3. December 2011 to February 2012: A rare example of current events triggering a genuine shift in public opinion, as Cameron’s EU veto, and the widespread positive coverage of it in the Eurosceptic parts of the press bring the Conservatives a short lived win over UKIP, enough to bring their support briefly level with Labour.

Phase 4. March 2012 to December 2012: The Conservatives’ support collapses sharply in the spring, while Labour’s rises. Labour moves from a dead heat to a ten point lead in a few months. While the “Omnishambles” budget, and other political mis-steps such as the bungled deportation of Abu Qatada are possible triggering events, it is also possible that the Conservatives’ Christmas 2011 rally was unsustainable, and that they were bound to revert to their equilibrium position once normal service resumed. Things level off by the summer, and for the rest of the year the Conservatives languish around 10 points behind Labour. UKIP continue their slow but steady rise, and by the end of the year are competing with the Lib Dems for third place.

Phase 5. January 2013 – June 2013: UKIP become the big story as their support surges ahead, and they deliver an impressive and largely unexpected haul of local election victories. The wave of positive media coverage that ensues further propels them upwards, to a peak of close to 15% at midsummer. The UKIP surge is reported largely as a Conservative problem, but the polls tell a different story: both Labour and the Conservatives lose ground as UKIP advance. UKIP are more than just a Conservative revolt, as our sister blog UKIPwatch has explained.

Phase 6. July 2013 – present: UKIP fall back a little as the media move on to other stories, but the insurgents keep much of the new support they have picked up and remain well ahead of the Lib Dems in third. The Conservatives recover their lost ground, but Labour do not, resulting in a narrower lead of 5-8 points over the Conservatives. By the autumn, the pattern is set and has continued to date.

Six phases in four years suggests that, with over a year to go, there is still time for another twist in the tale. While this is true, the scope for large shifts ahead of the election is narrowing every month. Who is going to change their minds? The ten percent bloc of the electorate that switched from the Liberal Democrats to Labour at the start of the Parliament shows few signs of having second thoughts, and, given their hostility to the government and its leading figures is almost equal to Labour’s, there is little reason to think they will in the near future. Labour’s gains from this group look secure.

At the other end of the spectrum, the ten percent chunk of the electorate who have switched their allegiance to UKIP also look tough to convince. These voters are angry, disaffected and deeply hostile to the whole political mainstream. It is possible that concerns about the futility of a UKIP vote in most local constituencies will induce some to drift back to the mainstream, but we wouldn’t bet on it. Given their generally bitter outlook, such voters may prefer staying home than backing one of the hated “LibLabCon”.

The balance therefore lies, as it often does, with the mushy middle and the economy. The likeliest driver of a shift in sentiment over the next year would be if sustained economic recovery started to be felt in the pockets, and the minds, of uncommitted voters. Conservative pundits are fond of likening 2015 to 1992 – an election when a large Labour lead evaporated due to lasting public concerns about the opposition party’s ability to manage the economy. They should also give thought to the sobering possibility that 2015 will instead play out like 1997 – when an unpopular Conservative incumbent waited in vain for a surging economy to deliver a rebound in their support. The same combination of buoyant economic numbers and stagnant poll numbers is playing out again today, and every month it continues, the brows in Conservative Central Office will be furrowing a little deeper.

P.S. In an excellent blog on Lib Dem prospects, Lewis Baston has queried whether our method is a little bearish on the party. We agree with many of his points, and will return to this issue in more detail in a future post. Our modelling choices do look a little harsh on the Lib Dems at present, but this was not so clear when we set up our polling model in 2010, and we are reluctant to confuse our analysis by changing our methods half way through a Parliament. The choice of model does have some impact on overall Lib Dem support levels, but it has no impact on the broad trend: the Lib Dems lost over half their support in their first year in government and have, to date, found no effective methods to bring their national popularity back up again. However, we agree with both Lewis and Stephen Tall that the national poll numbers are misleading for the party, whose fate will be decided, more than those of the other parties, by their local constituency campaigns.