This blog post, by Dr Robert Ford, Dr Will Jennings and Dr Mark Pickup is the thirty-second in a series of posts that report on the state of the parties as measured by opinion polls. By pooling together all the available polling evidence we can reduce the impact of the random variation each individual survey inevitably produces. Most of the short term advances and setbacks in party polling fortunes are nothing more than random noise; the underlying trends – in which we are interested and which best assess the parties’ standings – are relatively stable and little influenced by day-to-day events. If there can ever be a definitive assessment of the parties’ standings, this is it. Further details of the method we use to build our estimates of public opinion can be found here.

After a brief Christmas ceasefire, Britain’s politicians have returned to combat in earnest, with the early shots of 2014 reflecting the mood of the times: help for the poorest struggling with eroding wages, more broadsides against Britain’s little loved banks, and a high crescendo of panic about migration leading to crushing disappointment in some parts of the media (and UKIP) when the promised tidal wave of Romanian and Bulgarian benefit seekers failed to materialise.

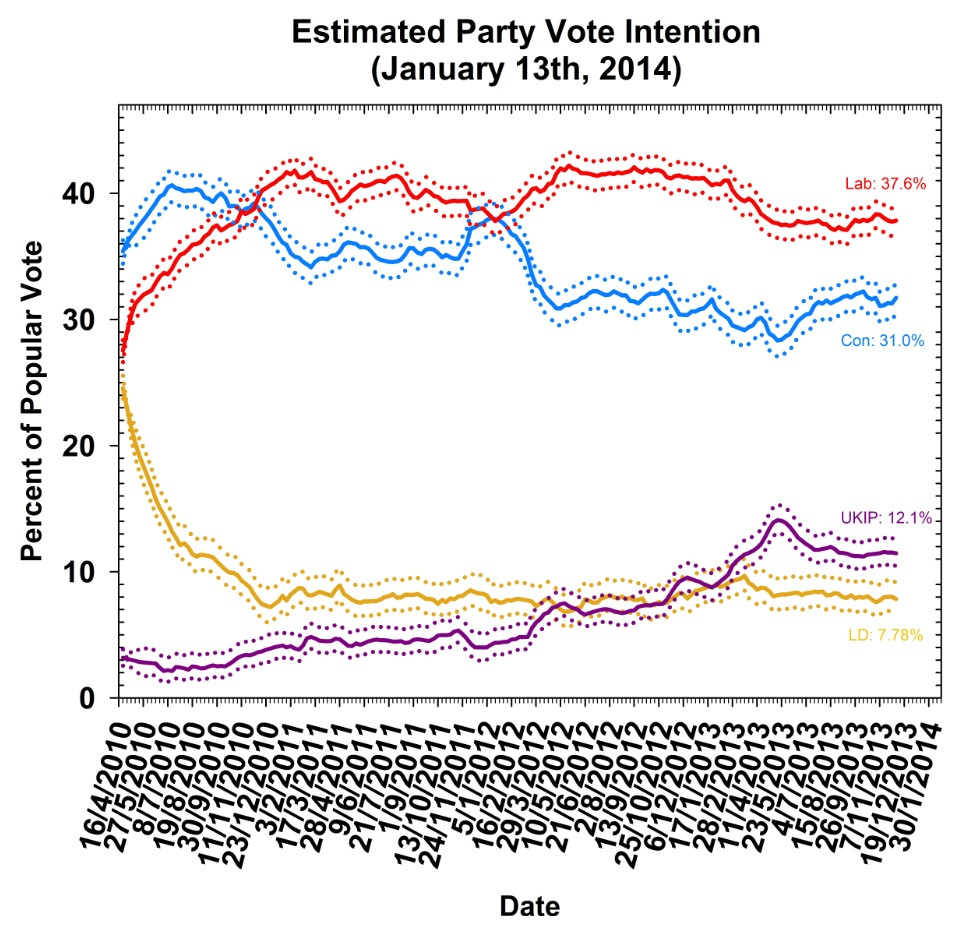

How have the parties fared over this not-so-festive season? Pretty much as they did in last month’s report. We estimate Labour at 37.6%, down 0.2% on last month and the seventh straight month our estimates have placed them in the 37-39% range. The Conservatives tick up a measly 0.1% to 31.0%, so they also continue to hold steady at the same level seen since the early autumn. The Lib Dems come in at 7.8%, continuing a flat line trend which extends all the way back to early 2011. UKIP move up 0.2% to 12.1%, also in line with the figures for the past five months or so.

The public’s mood currently is settled into a steady state, with support split across four parties and Labour holding a modest, but consistent lead. Neither the economic recovery, nor the A2 migration “crisis”, nor the various much trumpeted policy initiatives floated by government and opposition have yet had any discernible impact.

No news on the polling front is better news for Labour than it is for the Conservatives. With a general election now less than 16 months away, every month without movement on the polling front brings them a small step closer to defeat. Our research into historical polling (with Stephen Fisher of Oxford and Christopher Wlezien of University of Texas-Austin) suggests that British polls become steadily more predictive of election outcomes starting from about 18 months out from a general election, particularly for the Conservatives. With each month that ticks by without movement, the Conservatives’ prospects of turning things around become a little weaker, and Labour’s prospects of holding on to polling day become a little more certain.

As polling day gets closer, the ticking clock will loom larger in the parties’ minds, too. If the Conservatives poll share remains static as evidence of a robust economic recovery continues to pile up, pressure will build on David Cameron and George Osborne. Conservative backbenchers and activists who currently shower them with plaudits for the return of growth will soon turn against them if this growth does not deliver new voters. In particular, the tensions arising from UKIP’s continued double digit polling will only worsen, as the party divides between those who insist success requires imitating Nigel Farage and stealing his proposals, and those who worry that “out UKIP-ing UKIP” is impossible and damaging to the Conservatives’ credibility with moderate voters. Conversely, on the Labour benches, each successive month of steady leads will calm the nerves of those worried about Ed Miliband’s weak personal poll ratings, and anxious that the economic recovery undermines the credibility of the party’s focus on the “cost of living crisis”. Dissenters within the party are unlikely to raise their voices when they risk jeopardising a small but sufficient lead in polling, and each month of relative unity and harmony will help Labour’s image as a credible governing alternative, particularly if the Conservatives are wracked by conflicts over UKIP and Brussels.

Stable poll numbers are not great news for the smaller parties either. If their poll numbers continue to stagnate at alarmingly low level, rank and file Liberal Democrats may start to question the party leadership’s strategy of “divergence” within Coalition and call more loudly for out and out conflict with their Coalition partners or to exit the unhappy political marriage altogether. Stagnant poll numbers also hurt Nigel Farage’s argument that UKIP are the rising force in British politics – rising poll numbers are a key source of the oxygen of publicity UKIP need as an outsider force, and the radical Eurosceptics’ support levels are not yet healthy enough to convince many that their insurgency can be converted to Westminster power under Britain’s unforgiving first-past-the-post electoral system.

Labour can take some comfort from the status quo, which suits them, but they should not fall into the trap of thinking it cannot change. The story of polling since 2010 has been one of long periods of calm weather, interspersed with stormy spells where the political climate changed rapidly: late 2010 – when the Lib Dems slumped and Labour surged; early 2012, when the Tories briefly closed the gap before slumping back following the “omnishambles” budget; and spring 2013, when (as Anthony Wells notes) the Conservatives halved the gap on their Labour rivals. There will be plenty of weather-making political events in 2014 – the spring Budget, the first when George Osborne will be in a position to hand out good news (and maybe some giveaways); summer’s local and European Parliament elections and autumn’s Scottish independence referendum. A busy year is in prospect for politicians, pollsters and pundits.

Robert Ford, Will Jennings and Mark Pickup