This blog post, by Dr Robert Ford, Dr Will Jennings and Dr Mark Pickup, is the thirtieth in a series of posts that report on the state of the parties as measured by opinion polls. From now onwards, Manchester Policy Blogs will be posting Polling Observatory updates on a regular basis, alongside the well established Ballots and Bullets blog. A more detailed introduction to the work of Polling Observatory will appear here in due course.

By pooling together all the available polling evidence, the aim is to reduce the impact of the random variation each individual survey inevitably produces. Most of the short term advances and setbacks in party polling fortunes are nothing more than random noise; the underlying trends – in which the authors are interested and which best assess the parties’ standings – are relatively stable and little influenced by day-to-day events.

If there can ever be a definitive assessment of the parties’ standings, this is it. Further details of the method used to build the estimates of public opinion can be found here.

As the dust settles after conference season the state of support for the parties as 2014 approaches appears to have crystallised a little.

Despite the supposed conference bounces and bumps that media commentators identified following Ed Miliband’s energy price freeze pledge and David Cameron’s conference speech, when all the underlying noise has been accounted for there has only been a slight shift since the end of the summer (and – as we have noted before – vote intentions for the main parties had been stable for some time before this).

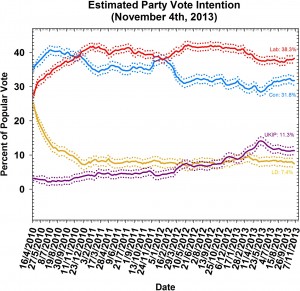

If there is a winner from conference season, it is Labour, who after making the political weather ever since putting energy prices top of the political agenda have seen their support increase to 38.3%, up one point from our last report at the time of their conference in mid-September.

This marks a reversal of the recent trend of a decline in Labour support. Despite the fanfare around the Conservative Party conference and the Godfrey Bloom side show at the UKIP conference, support for both parties has been static in the last six weeks – with no sign of a lasting conference bounce.

Support for the Conservatives stands at 31.8% (with no change since our report at the time of their conference in late September), and UKIP at 11.3% (unchanged). There is worse news for the Liberal Democrats who now stand at 7.4% (down 0.3 points since their conference) – close to the all-time low for this parliament.

Despite efforts to put clear blue water between them and their coalition partners – such as on green taxes on energy and qualifications for teachers – they are still paying the price for their abandonment of key election pledges early in the parliament.

It is increasingly significant that the UKIP vote has been consistently higher than the Lib Dems for six months now – suggesting that there has been a rebalancing of electoral support for the third and fourth parties.

In previous posts, we have sought to urge caution on the lazy anecdotal use of past precedent to predict the outcome of the general election due to be held in 2015. We are keen forecasters ourselves, and some of these important qualifications will also apply to statistical models that look to forecast the likely swing towards or against the governing and opposition parties as the election nears.

It is not uncommon for the statistical relationships that underpin these forecasts are context-variant. In other words, the economy might be a critical factor in one election but not in the next. Or leader ratings might matter for some parties but not others. Or voters might move back towards the governing party late on for some election cycles, but not others.

In short, aphorisms such as ‘it’s the economy stupid’ and ‘leaders matter’ are based on sound political science, but may not always hold and may lead forecasters to go badly astray when predicting the result. They also provide journalists and opponents a convenient stick to beat parties and their leaders with, when the foundations of electoral support are often more nuanced.

There are several reasons why forecasts for 2015 might not stick to the expected script that the Westminster Village has been reciting so far.

Firstly, it is undeniable that both the Conservative and Labour parties have a much lower ‘ceiling’ than in past elections. The Conservatives last won over 40% of the vote in 1992 (and Labour in 2001), and have not looked likely to do so in 2015 so at any point in the current parliament. They would likely have to beat this figure to secure a majority.

Yet the party still suffers from an image problem with large swathes of the electorate and has done little to widen its appeal while in office. This makes the prospect of a large final year swing towards the government improbable despite the historical trend for mid-term movement away from the government in the polls to return as Election Day nears.

Labour’s prospective pool of support has also looked much lower than its time in opposition during the 1987-1992 and 1992-1997 election cycles, where its poll numbers exceeded 50%. It cannot count on protest votes against the coalition because of the presence of UKIP, and its traditional base is shrinking, and also vulnerable to the challenge from Nigel Farage’s party.

Secondly, it is over-simplistic to suggest that a growing economy will assure a Conservative victory. It would certainly make it more likely, given that many people will be better off as a result, but it still depends on who benefits from the economic recovery.

Personal (‘pocketbook’) economic judgments have been shown to be a significant determinant of voting. Even then, parties that have overseen sustained periods of economic growth are not always rewarded by voters. This perhaps explains why the Labour Party have been keen to push the economic debate towards the question of living standards (and the cost of living) rather than focus on the Coalition’s record on reducing the deficit and the impacts of austerity cuts.

While much of the public still blame Labour for the economic problems left after the financial crisis, they also are strongly of the opinion that the Coalition is handling the economy badly. This again points to the argument that the sort of pro-government swing experienced at past elections will have to be achieved against much stronger headwinds.

Thirdly, David Cameron has tended to enjoy a comfortable lead over Ed Miliband in survey questions both about the ‘preferred Prime Minister’ and leader approval or satisfaction. Cameron also receives much more positive evaluations on his performance from supporters of his own party. Miliband has not made an impact on substantial parts of the electorate.

For some, this state of affairs might point towards a clear-cut advantage on the basis of the importance of party leaders for voters making up their mind late. However, these advantages are observed in a context where all of the party leaders in Westminster have had persistently negative net ratings for the past three years. Indeed, Cameron currently has lower approval ratings (36%) than the St-Remy brandy-swigging and crack-smoking Mayor of Toronto, Rob Ford (44%) (no relation) [HT @JoeTwyman].

It is worth remembering that Cleggmania in 2010 stemmed from the public’s previous relative lack of exposure to Nick Clegg. If Ed Miliband is similarly able to put in a strong performance on the campaign trail and also during the election debates that surprises the expectations of voters, it may deliver a last-minute bounce and negate the recent trends.

In short, 2015 remains difficult to call, and it will be a challenge for any party to win a workable parliamentary majority.

[…] Original source – Manchester Policy Blogs […]