Ken Clark, Senior Lecturer in the School of Social Sciences, examines the Migration Advisory Committee’s recent report and discusses the need for place-based migration policy.

- The Migration Advisory Committee has persistently rejected calls for regional variation in the framework that regulates migration in the UK.

- It is clear that patterns of migration, and thus its geographical impacts, are not uniform across the country.

- Migration policy must consider geographical variation.

The Migration Advisory Committee’s (MAC) recent report on migration from Europe to the UK provides a comprehensive analysis of immigration from the EEA to the UK and presents recommendations on a post-Brexit immigration policy. The MAC notes how skilled European migrants have a more beneficial impact on the UK public finances compared to their unskilled counterparts and how skilled migrants are also less likely to cause a reduction in the wages of UK workers. The MAC’s resulting policy recommendation is that, irrespective of nationality (EEA or non-EEA), migration policy should favour skill and be much more restrictive towards those migrating to work in unskilled occupations. Such a policy would have major implications for workers from the Accession countries, those who joined the EU from 2004 onwards.

The MAC has persistently rejected calls for regional variation in the framework that regulates migration in the UK yet it is clear that patterns of migration, and thus its geographical impacts, are not uniform across the country. Workers from the new EU member states (the A8 or A12) tended to locate in poorer areas of the country where incomers have been less common. While previous migrant waves (eg Pakistanis and Bangladeshis or those from the Caribbean) were often drawn to industrial or public sector employment in London or the towns and cities of the Midlands and North of England, people from EU accession countries established new migrant geographies in more rural or coastal towns often associated with the food production or processing industry. The large increases in migration in such areas have been related to the Leave vote in the EU referendum.

Regional variation

In a recent paper in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (open access), my co-authors and I show that the labour market success of recent migrants to the UK depends in part on the types of areas in which they reside. In particular we focus on the level of deprivation in the local authority area. Using the government’s Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) which combines information from 38 different indicators across seven so-called domains of deprivation: Income, Employment, Health and Disability, Education Skills and Training, Barriers to Housing and Other Services, Crime and Living Environment. The government describes deprivation as covering “a broad range of issues and refers to unmet needs caused by a lack of resources of all kinds, not just financial”.

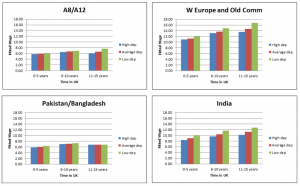

The question we address is whether migrants who locate in poorer areas have different labour market trajectories to those who locate in less deprived parts of the country. Using a statistical model we estimate the real wage growth of migrants from different areas of the world in different types of area: low deprivation, average deprivation and high deprivation. Figure 1 below illustrates the results for four migrant groups: the Accession migrants (A8/A12), those from Western Europe (including the original EU members) and the Old Commonwealth (Australia, Canada, New Zealand etc), Pakistani and Bangladeshi and Indians.

Figure 1: Real hourly wages for immigrant groups by local deprivation

Source: Author’s calculations from UK Labour Force Survey data

The figure illustrates a number of features of the labour market experience of recent migrants to the UK. First, and consistent with the MAC’s analysis, there is a huge difference in the absolute level of the hourly real wages earned by different groups. Migrants from Western Europe and the Old Commonwealth can earn up to double what A8/A12 or Pakistani/Bangladeshi migrants do. This partly reflects differences in skills and qualifications but also the industries in which migrants work and the potential impact of racial discrimination. Second, and unsurprisingly, across all groups wages tend to be higher in less deprived areas. Third, in areas which are more deprived wages grew more slowly across the first 15 years that migrants spent in the UK. Specifically, wages for A8/A12 workers in the least deprived areas with 11–15 years in the UK were 29% higher than those with 0–5 years. The equivalent figure for those in the most deprived areas was 5%. In other words, wage growth over the first fifteen years in the English labour market was almost six times higher in the less-deprived areas.

What this means for policy

Why does this matter? Discussions of the economics of immigration, whether in the academic literature or in the policy sphere, often treat the labour market as geographically homogenous; however it is clear that the prospects of workers, whether migrants or not, in some parts of the country are considerably worse than in others. There are two sides to this.

- First, when assessing the fiscal impact of immigration we need to note that opportunities for migrants to earn (and hence pay tax) are not the same in every part of the country.

- Second, underlying regional disparities in income and other aspects of deprivation are serious and persistent in the UK and migration policy, properly constituted, could view the influx of workers as an opportunity to address such inequalities, perhaps through measures such as a boosted Migration Impact Fund.

Either way, policy which is more attuned to geographical variation and the importance of place for the experience of migrants is essential.