How can the UK Government best tackle ethnic disadvantage? Dr Rob Ford looks at why a targeted approach aiming to tackle the problem directly could be politically dangerous.

Discrimination is a serious problem in Britain. A wide range of research shows ethnic minorities suffer disadvantages in university applications, in the labour market, in the housing market and in the workplace. Careful work by researchers has shown that these disadvantages are often down to discrimination alone – some white decision makers will prefer a white candidate over an equally qualified ethnic minority candidate. Offering targeted government assistance to minorities at the sharp end of such discrimination offers a means to combat discrimination and persistent disadvantage, and correct a major social injustice. But proponents of such policy face a major obstacle: public opinion.

We used specially designed survey experiments to test how public views of various welfare policies were influenced by which groups they targeted. We looked, firstly, at support for the principle of redistribution – the idea that reducing inequalities between different groups in society is something government ought to do – and at practical policies which could be used to bring about that goal. In both cases, we found the same pattern: high public support for both the principle and practice of redistribution targeted on grounds of wealth or social class, but dramatically lower support when the same principles and policies focussed on disadvantaged ethnic minorities.

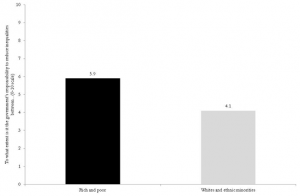

Figure 1: Mean support for redistribution between rich and poor, and between whites and ethnic minorities

Figure 1: Mean support for redistribution between rich and poor, and between whites and ethnic minorities

Source: Ford and Kootstra (2015); data collected by YouGov in 2011

In our first experiment, we randomly split our sample in two. Half were asked whether they thought it was the government’s responsibility to reduce inequalities between the rich and the poor, the other half were asked the same question about inequalities between whites and ethnic minorities. Figure 1 shows the results. The British public are quite keen to see government action to reduce economic inequalities, giving an average score of just under 6 out of 10 for the idea, on a scale where scores above 5 indicate support and scores below 5 indicate opposition. When the focus switches to ethnic inequalities, support drops sharply. The mean score falls to 4.1, indicating the average respondent opposes the principle of government action to reduce ethnic inequalities.

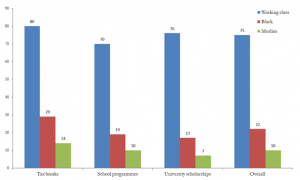

In our second experiment, we moved the focus from principles to practice. We asked people for their views on four “equal opportunities” policies designed to provide a leg-up for disadvantaged groups: tax breaks for businesses locating in areas with a large target group population, extra money for schools with a large target group population, and special university scholarships for children from the target group who achieve good grades. We randomly assigned people to be asked about one of three target groups: working class, black and Muslim. Figure 2 shows how targeting influences the proportion of respondents expressing support for each policy. In each case, support for assistance targeted at the working class is very high – 70-80 per cent. However, support for identical assistance policies targeted at black Britons is far lower – 17-29 per cent – while support for assistance targeted at Muslims is lower still – just 7-14 per cent of our sample. The British public strongly support assistance targeted at the working class, but oppose similar policies targeted on ethnic grounds.

Figure 2: Share of respondents supporting opportunity enhancing policies, by target group

Figure 2: Share of respondents supporting opportunity enhancing policies, by target group

Source: Ford and Kootstra (2015); data collected by YouGov in 2011

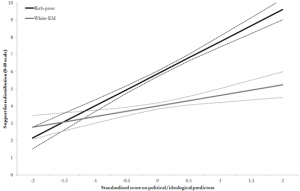

Two big factors help to account for the relative unpopularity of ethnically targeted policy. Firstly, traditionally left wing people – those concerned about inequalty and keen for government to do more to help the disadvantaged – are much less enthusiastic about such policies than they are about class or income targeted policies. As figure 3 below illustrates, right wingers are equal opportunity opponents – they dislike redistribution from the rich to the poor equally as much as redistribution from whites to ethnic minorities. It is left wingers who discriminate between the two principles: they strongly back rich-poor redistribution but have little enthusiasm for ethnic redistribution. It is a similar story with the policies we examined. Ethnically targeted policies are do not have a strong support base from their natural left wing constituency.

Figure 3: Left-right ideological views and support for redistribution of income from rich to poor, and from whites to ethnic minorities.

Figure 3: Left-right ideological views and support for redistribution of income from rich to poor, and from whites to ethnic minorities.

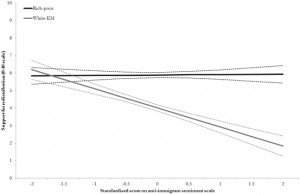

Secondly, even though our questions did not mention immigration at any stage, there was a strong link between our respondents’ views about immigration and their attitudes to ethnically targeted assistance, as figure 4 illustrates. Those who were hostile to immigration and immigrants were also totally opposed to ethnic targeting. We don’t know if such opposition is because anti-immigrant respondents thought such policies would benefit a group they dislike, because they worry that such policies would attract more migrants to Britain or for some other reason. Whatever the reason, the link between immigration attitudes and ethnic policy makes the latter a very tough sell, as opposition to immigration is widespread in Britain.

Figure 4: Views about immigration and support for redistribution of income from rich to poor, and from whites to ethnic minorities.

Figure 4: Views about immigration and support for redistribution of income from rich to poor, and from whites to ethnic minorities.

The high level of public opposition to ethnic targeting make such policies a tough sell as a solution. Traditionally left wing voters who normally support welfare spending are not enthusiastic, while anti-immigrant voters are strongly opposed. What should policymakers looking for new tools to fight the effects of ethnic discrimination and disadvantage do? One option would be to try and mobilise support from traditional left wing voters by getting them to see such policies as an essential part of the fight against inequality. Ethnic targeting is little discussed and seldom used in Britain, so the low enthusiasm of left wingers may be the result of unfamiliarity. However, the example of America, where ethnically targeted “affirmative action” policies have been part of the political debate for many decades is not encouraging: such policies remain very polarising and attract much less support than income or class targeted assistance. In addition, the strong connection between immigration anxieties and opposition to ethnic targeting will complicate building support for such policies so long as migration remains high on the political agenda, as it has been for much of the past decade.

There is a paradox in our findings, which policymakers fighting ethnic disadvantage may need to embrace. A university scholarship policy targeted at all working class children casts a much wider net than one targeted at disadvantaged ethnic minority children: all disadvantaged ethnic minority kids would be eligible, as would a large number of white kids. The more comprehensive approach would be more expansive, and expensive, yet it also enjoys much higher public support. As a result, it may be better to fight ethnic disadvantage by setting up broader, class or income based policies which win higher public approval, and then working to ensure fair ethnic minority access to the benefits of these policies. For, as far as British voters are concerned, going big in the fight on inequality is much more popular than going narrow.

- The views expressed in this article are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE).