The Government’s Industrial Strategy will be the flagship domestic reform programme of Theresa May’s administration. As Brexit realities begin to bite, it could also make the difference between success and failure across entire sectors of the UK economy.

On the launch day of our joint independent Industrial Strategy Commission with the University of Sheffield, Policy@Manchester Co-Director Professor Diane Coyle writes on the wider context and pressing urgency of creating an Industrial Strategy that works for all.

- Other advanced economies have long history of industrial strategies

- Around the world, government involvement in innovation has proved a success in theory and practice

- Brexit vote will amplify systemic challenges to key sectors of UK economy

- Only an effective Industrial Strategy will enable UK to overcome immediate challenges and build long-term success

It will be a long time before the effect of the Brexit vote on the UK economy become clear, as this will depend on how trade negotiations go and how business investors respond to the uncertainty. But the political shock caused by the vote has brought about one rapid and long overdue policy response: the revival of industrial strategy. The pattern of voting brought home to politicians (and others) has nothing else has the consequences of long-term economic decline in some regions of the UK. The ‘left behind’ voters to a large degree live in ‘left behind’ places where traditional industries long ago closed.

Since the neglect of the National Economic Development Office (‘Neddy’) since Mrs Thatcher’s first, 1979, election victory, and its eventual closure, Britain has been unique among both developed and emerging market economies in not having a strategic industrial policy. Some countries, such as the Netherlands, still even retain the idea of ‘planning’, a wartime legacy, in the title of their economic strategy institutions. But even the US, where policymakers never speak of industrial policy or strategy, there has been consensus about the role of the state in favouring certain kinds of research and development, and in the use of public procurement to favour American technology.

Creating Markets, Supporting Innovation: The role of government

Economic theory indicates some strong rationales for government involvement in innovative industries. Basic research is a public good, and one that that will always be under-provided by the private sector as private investors cannot capture the whole return. Government bodies are needed to co-ordinate technical or legal standards that allow markets to grow and reach efficient scale. The degree of uncertainty in early-stage research and development requires patient finance, and public institutions have longer time horizons than private businesses. Investors also need some assurance that a market for their new products could exist, so government procurement can help bring markets into being.

An instructive contrast is presented by the computer industry on both sides of the Atlantic. In both the US and UK the pressure-cooker of war delivered important innovations in computing, whether at Bletchley Park or Los Alamos. Even in the years after the war, the British state’s effort continued through the Post Office – a technological leader in those days – and at the University of Manchester, where ‘Baby’ was the first computer to have an electronically stored program. But the British sense of joint purpose fizzled out, whereas in the US a combination of private enterprise and public procurement and subsidy sustained the industry, which delivered a continuous series of innovations. Economists such as Mariana Mazzucato have argued strongly that significant government involvement has delivered success in both computing and biotechnology in the US.

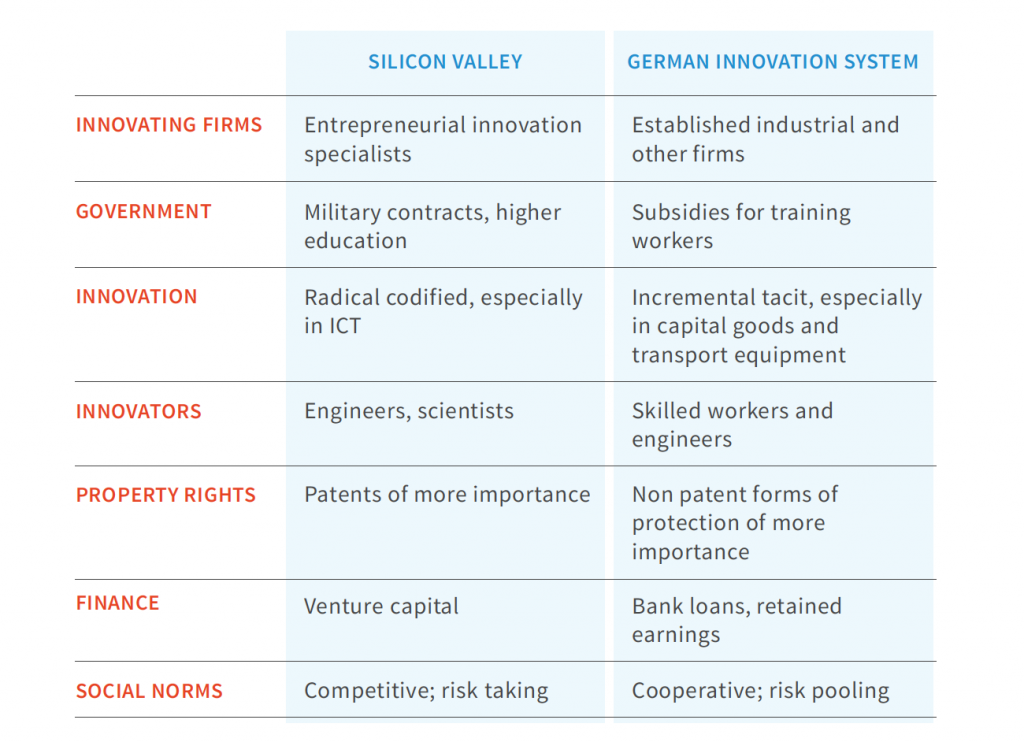

Likewise, the rapidly growing South and East Asian economies all deployed strategic state involvement as part of their ‘miracles’. The tools they used varied, ranging from export zones exposing domestic businesses to foreign competition while securing them a good home base in the domestic market, to state-financed research institutes, to ministerial direction of key industries. The common factor in all cases was a political consensus about the need for long-term government involvement. Successful industries are systems, linking a range of institutions with a common purpose. They differ from country to country (see comparison between American and German ICT support models, below); Britain will have to find one that works for its strengths and traditions in the post-Brexit world.

Industrial policy was tarnished in the UK by some significant failures in the 1970s. The policy became a way of rescuing failing industries rather than encouraging new ones. The idea that the government can ‘pick winners’ has been mocked ever since; but other countries seem able to accept the idea that there will be some failures. One of the lessons is that the institutional and governance framework is an important part of industrial strategy.

Industrial Strategy and economic challenges today

There is much to learn, or re-learn, if the UK’s fledging industrial strategy is to succeed. This is why today Policy@Manchester and SPERI at the University of Sheffield are launching an independent Industrial Strategy Commission, chaired by Dame Kate Barker.

It was the Brexit vote that brought home the long-term economic failure of the UK. Our level of productivity is substantially lower than in comparable nations. Export performance has been weak for years. The economic growth the UK has experienced has been unevenly distributed. The vote also raises the stakes in terms of future growth. Given the headwinds likely to be hitting our successful sectors, such as finance, cars, and pharmaceuticals, it is crunch time for finding a better policy framework.